NEW YORK — I.M. Pei, the versatile, globe-trotting architect who revived the Louvre with a giant glass pyramid and captured the spirit of rebellion at the multishaped Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, has died at age 102.

Pei’s death was confirmed Thursday by Marc Diamond, a spokesman for the architect’s New York firm, Pei Cobb Freed & Partners. One of Pei’s sons, Li Chung Pei, told The New York Times his father had died overnight.

Pei’s works ranged from the trapezoidal addition to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., to the chiseled towers of the National Center of Atmospheric Research that blend in with the reddish mountains in Boulder, Colo.

His buildings added elegance to landscapes worldwide with their powerful geometric shapes and grand spaces. Among them are the striking steel and glass Bank of China skyscraper in Hong Kong and the Fragrant Hill Hotel near Beijing.

His work spanned decades, starting in the late 1940s and continuing through the new millennium. Two of his last major projects, the Museum of Islamic Art, located on an artificial island just off the waterfront in Doha, Qatar, and the Macau Science Center, in China, opened in 2008 and 2009.

Pei painstakingly researched each project, studying its use and relating it to the environment. But he also was interested in architecture as art — and the effect he could create.

“At one level my goal is simply to give people pleasure in being in a space and walking around it,” he said. “But I also think architecture can reach a level where it influences people to want to do something more with their lives. That is the challenge that I find most interesting.”

Pei, who as a schoolboy in Shanghai was inspired by its building boom in the 1930s, immigrated to the United States and studied architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University. He advanced from his early work of designing office buildings, low-income housing and mixed-used complexes to a worldwide collection of museums, municipal buildings and hotels.

He fell into a modernist style blending elegance and technology, creating crisp, precise buildings.

His big break was in 1964, when he was chosen over many prestigious architects, such as Louis Kahn and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, to design the John F. Kennedy Memorial Library in Boston.

At the time, Jacqueline Kennedy said all the candidates were excellent, “But Pei! He loves things to be beautiful.” The two became friends.

A slight, unpretentious man, Pei developed a reputation as a skilled diplomat, persuading clients to spend the money for his grand-scale projects and working with a cast of engineers and developers.

Louvre controversy

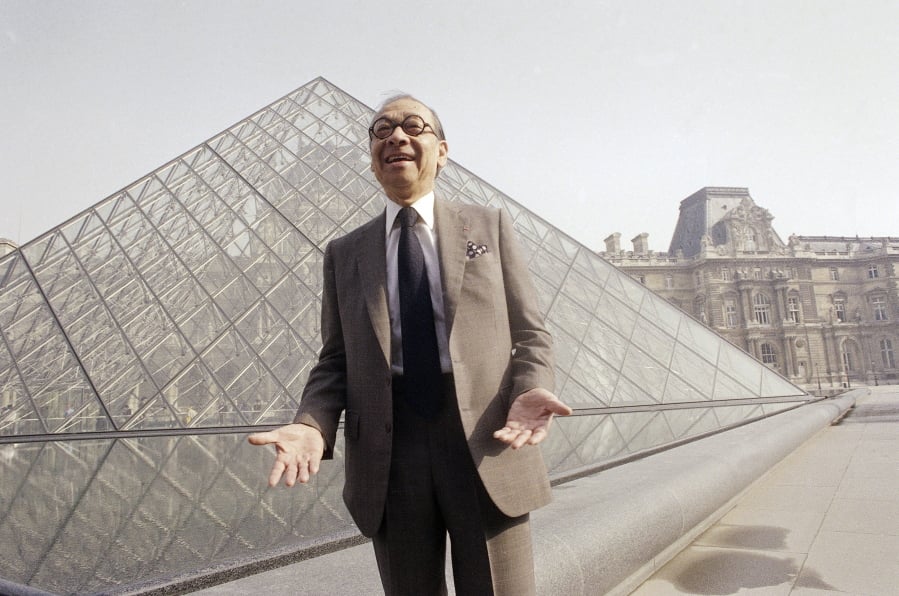

Some of his designs were met with much controversy, such as the 71-foot faceted glass pyramid in the courtyard of the Louvre museum in Paris. French President Francois Mitterrand, who personally selected Pei to oversee the decaying, overcrowded museum’s renovation, endured a barrage of criticism when he unveiled the plan in 1984.

Many of the French vehemently opposed such a change to their symbol of their culture, once a medieval fortress and then a national palace. Some resented that Pei, a foreigner, was in charge.

But Mitterrand and his supporters prevailed and the pyramid was finished in 1989. It serves as the Louvre’s entrance, and a staircase leads visitors down to a vast, light-drenched lobby featuring ticket windows, shops, restaurants, an auditorium and escalators to other parts of the vast museum.

“All through the centuries, the Louvre has undergone violent change,” Pei said. “The time had to be right. I was confident because this was the right time.”

Another building designed by Pei’s firm — the John Hancock Tower in Boston — had a questionable future in the early 1970s when dozens of windows cracked and popped out, sending glass crashing to the sidewalks, during construction.

A flurry of lawsuits followed among the John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance Co., the glass manufacturer, and Pei’s firm. A settlement was reached in 1981.

No challenge seemed to be too great for Pei, including the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, which sits on the shore of Lake Erie in downtown Cleveland, Ohio. Pei, who admitted he was just catching up with the Beatles, researched the roots of rock ‘n’ roll and came up with an array of contrasting shapes for the museum. He topped it off with a transparent tent-like structure, which was “open — like the music,” he said.

In 1988, President Reagan honored him with a National Medal of Arts. He also won the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize, 1983, and the American Institute of Architects Gold Medal, 1979. President George H.W. Bush awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1992.

Pei officially retired in 1990 but continued to work on projects.