Bobby Begay’s immediate family gathered at the longhouse in Celilo Village, a town of only 16 homes overlooking the mighty Columbia River, to begin the ritual of saying goodbye.

COVID-19 arrived at the Begay household in April 2020, and it stole the family’s patriarch in only a few weeks. Inside the longhouse, the family held a seven drums ceremony and ate a final meal – foregoing other traditions that night so they could be completed more safely amid the pandemic.

The day before, as the family met at a funeral home to dress Begay’s body in buckskin clothes and braid his hair, his daughter Daisy Begay turned to a family member and said she couldn’t breathe.

“I just remember being in such a dark place … I honestly thought I was going to die,” said the 32-year-old, who went on to spend 24 hours in the hospital with her own case of COVID-19.

“I thought my dad could be invincible, you know? And if he can’t beat this, what are my odds?”

Six people in the Begay household ultimately fell ill with COVID-19, emblematic of the disease’s outsize toll on Oregon’s Black, Indigenous and people of color populations. Throughout the pandemic, American Indian and Alaska Natives have recorded the third-most cases per capita and second highest death rate in Oregon; about 2,900 have been infected and 41 have died.

COVID-19 stripped Oregon’s tribal communities of one of their most beloved members – and the loss of Bobby Begay is still felt a year later. A member of the Yakama Nation, Begay, 51, was well-known within Celilo Village and throughout Oregon – and worked as a lead fish technician for the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, where he was remembered for his enthusiasm and humor.

“He was an incredibly generous person and had a willingness to share not only his harvest, but the message of why salmon, lamprey, and the river are central to our culture,” the commission wrote at the time of his death.

Begay was the only resident of tiny Celilo Village to die with COVID-19. His family has spent the past year coming to terms with his absence, and the community itself is only now beginning to envision life after the pandemic.

“My dad’s teaching to us was, ‘You don’t cry for me. Don’t hold me back,'” his son Steven Begay, 27, said. “His favorite saying was, ‘Life goes on.’ And you know, that’s how we live today. My life is still going on.”

• • •

Bobby Begay’s wife, Megan, 44, knows the day COVID arrived at their home – April 6, 2020.

“I can tell you the exact dates because I have it all charted,” she said. “But you don’t ever expect it to happen to you. We’re all invincible on some level.”

Megan, who met her husband through their fishery work at Bonneville Dam in the late 1990s, moved to Celilo in 2003 and into the family’s home with Bobby and his two children. They later had two children of their own, and eventually a granddaughter as well.

Last April, she watched as five of those family members got sick one by one.

Steven couldn’t get out of bed, had chills and a fever. Then her husband got sick. And then Daisy.

Megan Begay gradually realized she was losing her sense of taste and smell. That lasted for 10 days and was her only symptom. And then Steven’s daughter, Angeleah, 6 at the time, developed a rash all over her body, forcing them to take her to the emergency room.

Bobby and Megan’s son Henry, 14, was sick for 24 hours, while their youngest, Jackie, 11, exhibited no symptoms at all. She became Megan Begay’s “assistant caretaker.”

For weeks, they each stayed isolated in their rooms. Angeleah, who had recovered from her rash, began leaving notes and drawings for them on their doors.

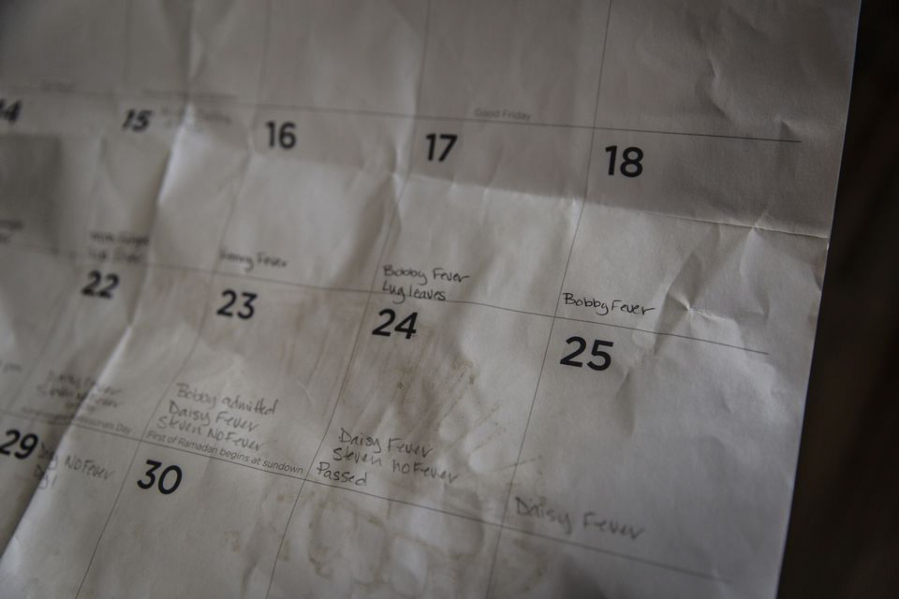

Jackie sat outside her older sister’s room to keep her company and Megan Begay slept in the hallway, keeping charts of temperatures, Tylenol distribution and marking each family member’s symptoms on a calendar.

On April 19, when Bobby Begay began having labored breathing, they took him to the Mid-Columbia Medical Center, where he was diagnosed with pneumonia and sent home. Four days after coming home, he was still complaining of pain in his chest and his breathing worsened.

Megan Begay called the doctor who urged her to call the fire department to come and check his oxygen saturation levels. By the time his levels were checked the following morning, his oxygen saturation was at 56 – a number that would normally render someone delirious.

He was immediately sent back to the hospital on April 23 and placed on a BiPAP machine, which helps push air into the lungs. The next day, as his condition worsened, the Mid-Columbia Medical Center decided to intubate him and prepared to transfer Begay to Portland.

But the transfer never went through. Instead, the hospital called and told Megan Begay to come immediately.

She got a sinking feeling inside and knew it couldn’t be good. She breathed hard, almost hyperventilating, and told Henry, “We need to get to the hospital.”

At the hospital, doctors said his heart stopped and they couldn’t revive him.

Bobby Begay died April 24, less than three weeks after COVID-19 hit the family.

Megan Begay held her husband’s hand one more time in his hospital room and her son sang a religious Wu00e0ashat song.

“It’s pretty quick,” Megan Begay said. ”

• • •

Celilo was once home to waterfalls that were used by tribal fishers for over 9,000 years to catch salmon, one of their native foods.

But in 1957, The Dalles Dam was built some 14 miles to the west and the falls along the Columbia River were gone within hours, now a distant memory to the oldest elders on the river.

Bobby Begay taught his son how to fish, how to go smelting, and how to hang nets – carrying on centuries-old traditions of their people on the Columbia River.

“I heard a lot of different stories,” Steven Begay said. “And, you know, just hearing all this sadness of all the other elders who came and talked about the falls, and how they stood on the rocks, watching it being covered, watching it disappear.”

Tribal elder and lifelong Celilo resident Karen Jim Whitford was 5 when the falls disappeared.

She is now one of about 80 people who call Celilo Village their home on a narrow quarter-mile patch of ground overlooking Interstate 84 and the Columbia River.

The longhouse is the focal point of the village and the people from various tribes who live along the Columbia River.

But since the pandemic, the sacred building has largely been quiet – the ceremonies, feasts, gatherings and religious Wu00e0ashat services put on hold indefinitely.

Today, Whitford carries with her the sense that she never got to honor the death of her nephew, Bobby Begay. Because of her age and the family’s illness last April, she was unable to attend the dressing, drum ceremony, last meal and burial for him.

“I had no closure to comfort myself, because this was part of our culture, our religion – the ceremonies that we’re supposed to do. And still today, we still don’t have closure,” said Whitford, whose husband, Fred, also became sick with COVID-19 but recovered. “We have no closure to heal.”

• • •

On two recent Fridays, Celilo Village began to get a glimpse of the future and a possible return to normal.

The longhouse, dormant through much of the pandemic since the immediate family gathered there to remember Bobby Begay, was transformed into a vaccination center for Native people along the Columbia River.

The clinic could have been held on tribal land miles away, but the Celilo Village longhouse made sense because of its central location and designation as the meeting place along the river. The Celilo WyAm Chief, Olsen Meanus Jr., was approached and the clinic was arranged.

More than 200 doses were made available through a partnership with One Community Health, a federally qualified health center, and Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission.

On Feb. 26, Karen Jim Whitford and her husband received their second doses of the vaccine. Daisy, too.

The same morning, Steven Begay sat in a chair just outside the longhouse as his wife, Rosey Suppah, administered the second shot to him, too, as part of her new position as a nurse with One Community Health.

As people from surrounding tribes filtered through the outdoor vaccination site throughout the day, Steven Begay left to meet his cousin and they returned with a pickup full of tubs of fresh smelts. Bobby Begay’s youngest two children, Henry and Jackie, began sorting through the fish, bagging it and handing it out as gifts to tribal members who’d been vaccinated or were just walking by.

“Natives taking care of Natives is kind of what we always preferred,” Steven Begay said in the days leading up to the event, recalling the lessons he’d learned from his father. “And there’s still a lot of Natives that don’t trust non-Natives, just because of their history.”

Daisy Begay recovered from her bout with COVID-19, but has been deemed a long-hauler, still exhibiting symptoms and experiencing shortness of breath almost a year later. One of the hardest things is convincing skeptics, who she said she still encounters in daily life, that COVID-19 is real.

“My dad just didn’t die from the flu. This is something else,” she tells them.

Steven Begay has recovered, too. And as the oldest son in the family, he has taken on some of his father’s roles.

“He always wanted me to be better than him, which I don’t think I am,” he said. “But I’m doing my best to be the better person of me. And I’m just glad that I got to learn as much as I could from him during the time I had with him.”

Steven Begay’s daughter, Angeleah, is now 7 years old. Every morning she used to wake up with her grandfather so he could make her breakfast, and she’d wait all day for him to get home from work.

Sometimes, he threw her around his neck – calling her a yu00e0amash, the Sahaptin word for deer.

She draws him pictures now, and she points them toward the sky for Bobby Begay to see.