Locals called the hot easterly wind that swept through in 1902 the “Devil Wind.” On Sept. 12, after 77 rainless days, it blew flames across the dry tinder of Southwest Washington. Even today, no one knows how the Yacolt Burn started — perhaps a careless campfire, a spark from logging equipment, a tossed cigarette, lightning?

No U.S. Forest Service existed yet, and the West was unprepared for fires, small or large. Two “rangers” were assigned to cover 2 million wooded acres in Southwest Washington, part of which is the Gifford Pinchot National Forest today. One, Horace Wetherell, a homesteader near Carson, accepted responsibility for the lower half that ultimately burned. His tale is the only official account of the Yacolt Burn.

Wetherell’s 30-years-after-the-fact report blames Monroe Vallett for carelessly burning slash east of Stevenson and letting it ignite timber along Stevenson Ridge. Neither Wetherell nor Vallett acted to stop the fire. The east winds fanned the flames west down the Columbia Gorge.

Weyerhaeuser corporate history places the blame elsewhere, explaining the fire burst out along the Washougal River valley when loggers burned stumps, farmers torched slash or fishermen abandoned campfires.

A third explanation claimed the fire originated near Yacolt. Yet another suggests embers floated across the Columbia from a fire in Bridal Veil, Ore. Most likely, the fire had multiple ignition points, given that parts of three counties burned. People escaped its rage rather than face it.

In 36 hours, the fire traveled 30 miles, creating its own weather system. Flames shot up 300 feet, forming 40 mile-an-hour gales. Sparks leapt a half-mile. Smoke turned the midday sky to midnight black. Darkness cloaked the skies as far north as Seattle and west to Astoria, Ore. Residents lit lamps. In Vancouver, the U.S. Army was told to protect property. A steamer navigated the Columbia by searchlight. A half-inch of ash blanketed Portland, which suffered $1 million in property damage when it was over.

While named after Yacolt, the flames stopped a half-mile short of the town. Its 15 buildings survived, but their paint blistered. Fearful residents spent the night in nearby creeks for safety.

The loss was fantastic and destroyed parts of Clark, Cowlitz and Skamania counties. Newspapers reported 146 families homeless. Farmers lost barns and livestock. Churches and schools burned. So did logging and mining camps. In all, 38 people died, although one estimate that includes Oregon losses puts the death count at 65.

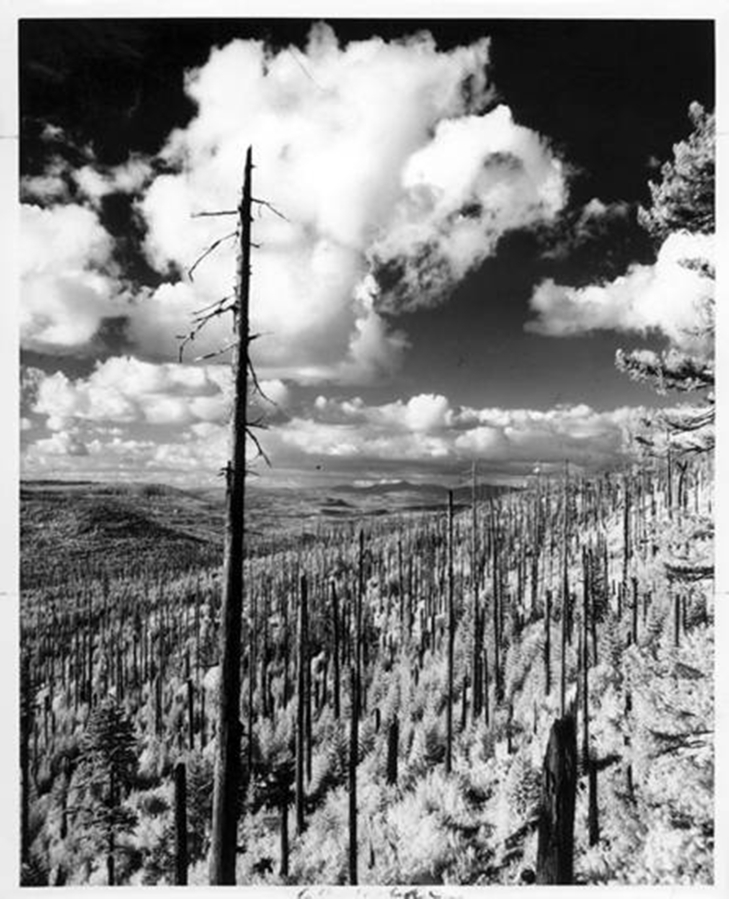

Southwest Washington lost 370 square miles of timber. (For comparison, Clark County is 656 square miles.) The Yacolt Burn caused a $12 million to $30 million loss in 1902 dollars. It wasn’t until the 2014 Carlton Complex Fire in Okanogan that it slipped into second place.

To prevent more large burns, Washington in 1903 added a fire warden position and severely restrictive burn rules. By 1908, its citizens helped create the Fire Protection Association, which created fire wardens and developed programs for fire prevention on private lands. Unfortunately, this didn’t help. The burn area flamed up again in 1929 and 1952.

The Yacolt Burn and other large fires in the West during the early 1900s pushed President Teddy Roosevelt to establish the U.S. Forest Service in 1905 and name Gifford Pinchot its leader.

Martin Middlewood is editor of the Clark County Historical Society Annual. Reach him at ClarkCoHist@gmail.com.