LOS ANGELES — When Christopher Plummer appeared at the Ahmanson Theatre in “A Word or Two,” his costar was a mountain of books. He was delighted to be in such excellent company.

The 2014 solo show had the feeling of a four-star general touring old battlegrounds before retiring to civilian life. But Plummer wasn’t going anywhere.

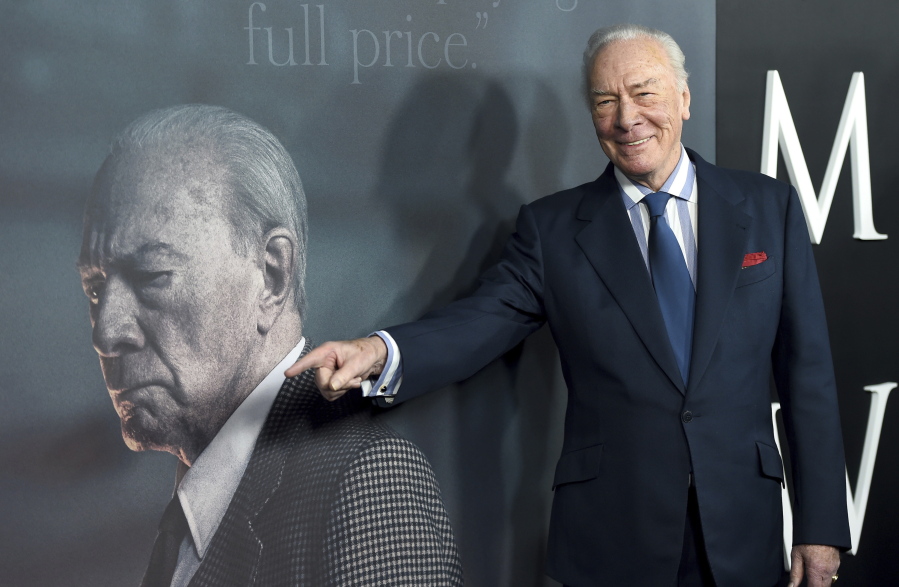

He had won an Oscar only two years earlier, his first, at age 82, for his slyly touching performance as a dad who comes out of the closet as a senior citizen in Mike Mills’ film “Beginners.” Still to come was another nomination for his portrayal of J. Paul Getty in “All the Money in the World.” Actors may pull back from the grind of the stage but they never stop working, if there’s a role they can make their own.

Plummer, who died last week at 91, wasn’t bidding his fans farewell when he made his return to the Ahmanson, where he had reprised his Tony-winning turn in “Barrymore” in 1998. He was saying thank you to the writers who had shaped and guided his talent.

“A Word or Two” was a paean to great literature and the power of the written word. Plummer, a Canadian exemplar of the classical stage, was a Shakespearean through and through. If he could be snarky about the fame that followed him from playing Captain Von Trapp in “The Sound of Music,” it was chiefly because those mountains he had climbed in the tragic repertoire — Hamlet, Macbeth, Iago, Lear — meant more to him than his celebrated march through the Austrian Alps of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musical.

It was through dramatic poetry that Plummer discovered his voice, which he developed into one of the supplest instruments of the modern stage. Playwrights guided him down this path but poetry, novels and enduring writing more generally nourished his quest.

Like Richard Burton, he was an intrepid stage animal in public and a bookworm in private. He was also bibulous like Burton and fondly recalled nights out carousing with Burton and other hard-drinking classical actors of the period, such as Jason Robards and Peter O’Toole, until health, sanity and marital injunction forced Plummer to clean up his act.

Wafting in the Shakespearean sublime one minute, sozzled in a dark pub with theater cronies the next, Plummer received an immersive education in both the majesty and the frailty of the actor’s life. To do justice to the grand tragic roles requires a knowledge of extremes, but longevity in the theater demands discipline.

Plummer didn’t let his destructive habits shortchange his career. But in “Barrymore,” he played another actor, John Barrymore, who waited too long to rein himself in. Summoning back to the stage the bleary-eyed thespian who destroyed his gift en route to becoming one of the first Hollywood superstars, Plummer paid homage and bore witness to a figure he understood only too well.

Drink was Barrymore’s undoing, and in the fictional setup of William Luce’s play, the actor is attempting to rescue his career with a stage comeback. Plummer captures both the pathetic hamminess of the old trouper who can’t remember any of his lines and the glory of the artist who is occasionally able to take flight on Shakespearean words before crashing back down to an empty theater.

When an actor of Plummer’s stature dies, it marks not simply the loss of a singular talent but the severing of a connection to an august tradition. The status of the classical actor, once regarded as the pinnacle of the field, has diminished as screens have expanded their monopoly on drama.

Great acting is judged today through close-ups that younger audiences are more inclined to view as clips on their pocket devices. The Method, in all its many manifestations, has won the cultural battle. Actors, training for the camera, are worried more about inner truth than polished technique. The road to psychological realism is presumed to cut through personal history.

Stella Adler, one of the great acting teachers of the 20th century, knew this was not just misguided but a misreading of Stanislavski, the source of the Method’s approach. Imagination is what must be mined, not childhood trauma. One should rise to meet the great dramatic characters, not bring them down to our petty level. Experience for an actor is invaluable, but it mustn’t function as a restraint. There are more things in heaven and Earth than are dreamt of in our limited biographies.