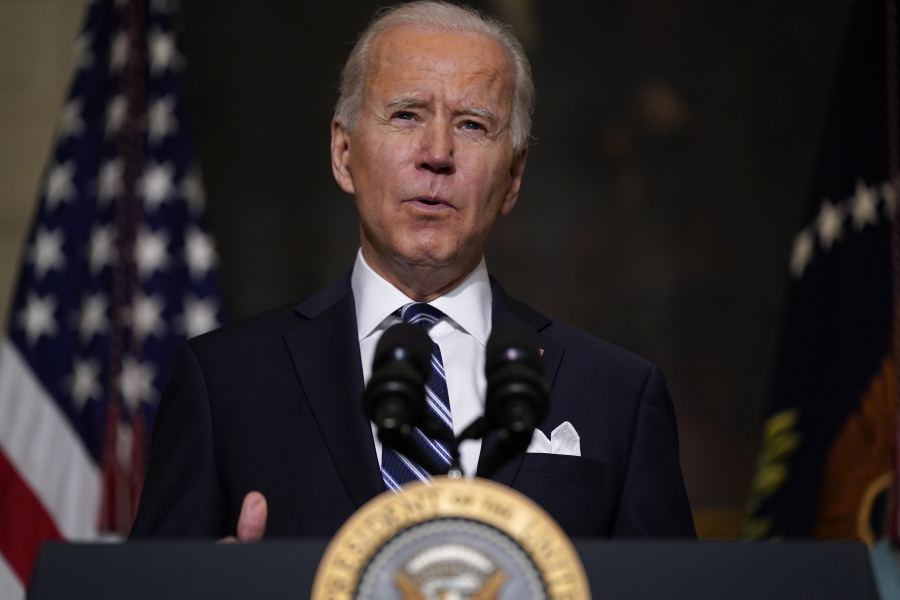

WASHINGTON – President Joe Biden’s tenure will be defined by his response to the coronavirus pandemic, an issue that stained former President Donald Trump’s term.

But that’s just part of the Trump health policy record that Biden now confronts. The new president is inheriting a unique mix of extraordinary and everyday policies at various stages of completion.

Trump’s most infamous unfulfilled health policy pledge, of course, was his lack of a comprehensive plan to replace the 2010 health care law, despite the president’s repeated promises and GOP lawmakers’ attempts to repeal it.

The Supreme Court is due to rule as early as this spring on the constitutionality of the law’s mandate to buy coverage and whether the law’s survival should hinge on keeping the mandate in place. The court appeared skeptical of Republican states’ challenge during arguments in November and Democrats may seek to make the issue moot through legislation, but an adverse verdict could throw the Biden administration into turmoil.

Such a ruling could also have cascading effects on policies that Trump hailed as personal successes, ranging from Medicaid work requirements to drug prices to transparency in hospital and physician prices.

A summary follows of what Trump accomplished, where he fell short of his goals and what Biden might undo.

At more than 400,000 deaths, the COVID-19 pandemic is one of the deadliest events for Americans in modern history, surpassing U.S. casualties in World War II. Experts estimate that as many as 40 percent of those deaths occurred in long-term care facilities.

While public health experts urged the use of quarantines and masks, Trump pushed to keep businesses open and tamp down panic. Rather than take the reins of a comprehensive national plan, the White House relegated much of the responsibility to states.

“In emergency management there are always multiple impacts — economics, housing, lives lost, mental health. … You have to pick and choose,” said Samantha Montano, an expert in emergency management at Massachusetts Maritime Academy. “If you look at the death toll crossing 400,000 in the last year, very clearly people’s lives were not the priority.”

Containing a crisis requires credible and consistent communication, which was often absent under Trump. Anthony Fauci, a former member of Trump’s coronavirus task force, told reporters on the Biden administration’s first full day that he finally felt he could speak freely.

The federal Operation Warp Speed initiative on vaccines and therapeutics did, however, make a smart multibillion dollar bet on mRNA vaccines, a novel technology developed with the help of U.S. scientists, which were more effective than most dared to hope and were authorized in record time. But vaccinations are lagging as regional health departments and medical providers struggle to get shots in arms amid a surge in cases.

The Trump administration did not apply lessons learned from prior pandemics, including earlier coronavirus outbreaks like SARS and MERS. Wartime powers were not fully utilized to increase manufacturing of supplies like protective equipment, as the administration trusted the markets to self-correct. Many remain in short supply.

The White House also did not appear to consult earlier pandemic preparedness plans laid out by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, according to University of South Carolina pandemic historian Nukhet Varlik.

The U.S. response was the “worst in the world,” Varlik said. “The result is absolutely horrific.”

The CDC and the Food and Drug Administration also stumbled in the early rollout of tests, dispatching flawed testing kits and waffling on oversight of commercial lab tests. The administration eventually rebounded, invoking some powers under the Defense Production Act to boost supplies and distributing tens of millions of rapid point-of-care tests to states and nursing homes.

With supply shortages still common, Biden directed his administration to use more powers under the DPA to fill the gaps.

Michael Mina, a Harvard University assistant professor of epidemiology and an advocate for more rapid tests, says Biden officials should shift the FDA’s interpretation of rapid tests. Ongoing confusion among scientists about the tests’ ability to identify useless fragments of the virus — versus cases that are actually infectious — is still undermining trust in their use, he said.

The recommendation by FDA and CDC to confirm most negative rapid test results with a traditional lab test is “off base,” he said.

“It’s a very simple story — the kinetics in terms of the clearance rate of real virus versus the RNA left over from the virus are just different,” he told reporters Friday. “And if we don’t appreciate that, then we’re going to keep confusing scientists.”

Republican efforts to replace the 2010 health care law ultimately fell short. But lawmakers did succeed in eliminating some high-profile provisions, including industry taxes and the fine for not having insurance.

The law is still at risk in the Supreme Court challenge, known as Texas v. California. The Trump administration declined to defend the law, instead joining Republican states in asking the justices to strike it down.

Democrats now have majorities in both the House and Senate for the first time since the session marked by the law’s enactment, giving them an opportunity to make changes and build on its foundation. Biden asked Congress to do that in his COVID-19 relief package, including a proposal to increase tax credits that subsidize monthly premiums.

He also proposed subsidizing COBRA coverage, which allows former workers to remain on their employer-sponsored health plans after leaving a job. That coverage can be expensive, though, since employers typically shield enrollees from a large portion of the cost.

Congress cleared surprise billing legislation as part of a year-end package in 2020 following years of work. The law is set to take effect next year, and will shield patients from receiving unexpected bills from out-of-network doctors at an in-network facility or in emergency cases.

The law establishes an arbitration process for resolving payment disputes between providers and health plans, and lays out the factors the arbiter could consider when picking between the two sides.

The Biden administration will need to issue regulations this year, largely on the dispute resolution process. Those regulations could affect how easy it is to use arbitration, and the procedural details set up by the administration could affect the system more broadly, said Katie Keith, a research faculty member at Georgetown University’s Center on Health Insurance Reforms.

“If arbitration is really easy to use, you’re not going to have as much of an incentive for insurers and providers to negotiate or for providers to go in network,” she said.

The Trump administration set forward a series of goals for reshaping Medicaid, but the policies were largely blocked by litigation or lack of support.

Former Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma advocated for states to receive block grants for their Medicaid funding in exchange for added flexibility, but efforts to implement this system were delayed. Verma approved Tennessee’s request to cap its funding just before exiting office this year, in a move that Biden will likely reverse.

Verma also granted approval of the first work requirements in the Medicaid program in 2018 in Arkansas, which led to over 18,000 enrollees losing health care before the program was blocked. Ongoing litigation has limited these requirements there and in other states, and new waiver approvals are unlikely during the Biden administration.

The fate of Medicaid work requirement waivers also now lies before the Supreme Court.

Trump was also successful in starting to unlock the secret box of prices negotiated among medical providers and insurance companies through two separate rules. The hospital industry challenged and lost a court case over a rule affecting disclosure of its prices, which took effect this year. A more wide-ranging rule for insurers takes effect in 2022.

But actions among hospitals have been spotty thus far, and it will be up to the Biden administration to enforce the rules. Price transparency could have far-reaching consequences if app and software developers can analyze and synthesize the data into actionable tools.

Trump’s drug pricing blueprint, on the other hand, went largely unfulfilled after being hamstrung by internal disputes and Trump’s own shifting priorities. After abandoning his campaign promise to let Medicare negotiate drug prices, Trump instead pinned his legacy on a series of smaller proposals, including many that were struck down in the courts or abandoned.

Among the most ambitious proposals was a demonstration setting Medicare outpatient drug prices at the lowest rate paid among other wealthy nations.

But a last-ditch effort to finalize the rule outside of normal procedure triggered its likely death in court. Biden is likely to drop the rule in favor of more aggressive tactics pursued by Democrats in Congress, which would also produce savings that could offset other expensive proposals — such as increasing health insurance subsidies.

The pilot is also at risk from a Supreme Court ruling on the health law, since it would be operated by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, which was created by the law.