Children have fared better than adults in the coronavirus pandemic, a fact that makes the development of vaccines for them a unique effort in the annals of medical science.

Historically, pediatric vaccines have focused on killer childhood diseases, but the pandemic has thrown a curve into that thinking. While the virus has been a deadly force among older adults, it’s been shown to be mild in the young with deaths relatively minimal.

That’s sparked an emerging debate among scientists about how critical it is that children be immunized. Some say the case for inoculating kids is less pressing, given that their outcomes tend to be so much better. Worldwide, the rollout of vaccines has prioritized older people and others at risk because of their health or occupation.

“Vaccines for polio, diphtheria and meningitis were all geared to eliminate the most dangerous diseases in children,” said Michael Hefferon, an assistant professor in the pediatrics department at Queen’s University in Ontario. “We now have almost the opposite. It’s a disease of adults, and the older you get the more sinister it is. Therefore children are less relevant.”

Almost 3.2 million children have tested positive for COVID-19 in 49 states that report cases by age, according to a March 4 report by the American Academy of Pediatrics. But at a time when more than a half-million COVID-related deaths have been reported in the U.S., only about 250 children have died in the 43 states that track mortality by age.

The debate comes as President Joe Biden is pressing for the return of all kindergarten through eighth-grade classes, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has said even teachers don’t need to be vaccinated if certain rules are followed. Meanwhile, a study in the journal Pediatrics this month found that just 0.4% of 234,132 people tested in New York City schools from October to December were positive.

The question shouldn’t just be can you inoculate children safely and effectively, but also “why you’re doing it,” said Hefferon, who says some regulators may question the need for emergency use. “If you take it that grandma and grandpa are going to be vaccinated on a mass scale under present plans, why vaccinate children? That’s kind of a moral dilemma to be considered.”

Are you doing it for the kids, he asks, or for everyone else?

Proponents of COVID vaccines for children offer another view. With a third to half of adult Americans in recent polls saying they probably won’t get the shots, they say vaccinating 25 million Americans ages 12 to 17 could help curb transmission to those at highest risk and speed up the race to herd immunity.

“You’ve got to be able to limit transmission by children,” said Sanjay Jain, a pediatrics professor at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore. “And some children do get serious illness from the virus. Is it needed? The answer is absolutely yes.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics agrees. In a Feb. 25 letter to the White House and top U.S. health officials, the group’s president, Lee Savio Beers, wrote that having a COVID-19 vaccine for children “is essential for our nation to end the pandemic.”

Children “have suffered throughout the pandemic in ways both seen and unseen,” she wrote. “We cannot allow children to be an afterthought when they have shared so much burden throughout this pandemic.”

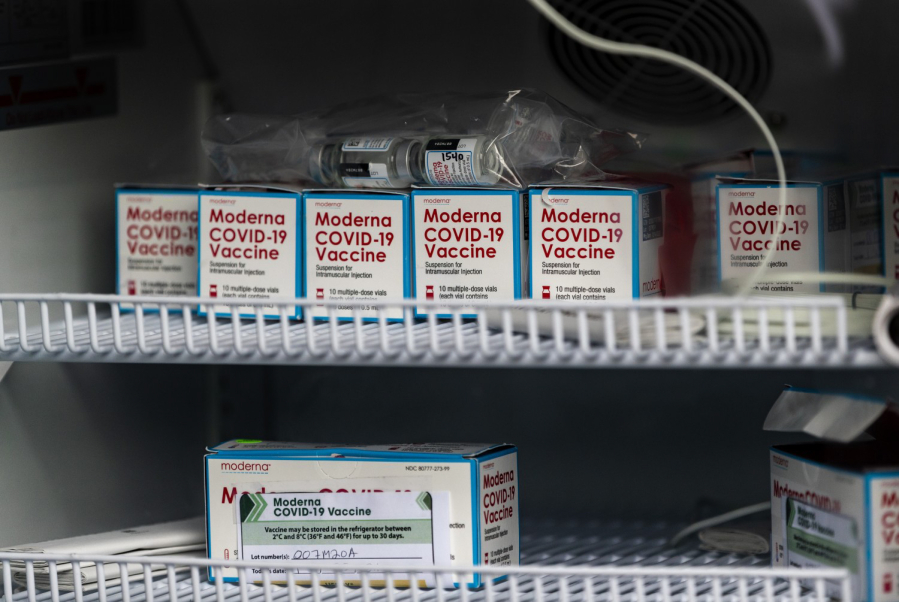

Meanwhile, Johnson & Johnson, Moderna Inc. and the Pfizer Inc.-BioNTech SE partnership are all making fast progress in trials in children ages 12 to 15 at a time when mitigation measures are slipping and a new school year is just six months away.

“For children 12 years of age and up, there will be a vaccine available before the next school year,” said Robert Frenck, director of the Vaccine Research Center at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and a principal investigator for the Pfizer trial. “Just looking at the time lines, it’s probably more likely the end of 2021 to early 2022 for younger kids, but maybe it’ll go a little faster than that.”

While some parents are understandably shy about putting their children in such a trial, Frenck said he has had few problems getting volunteers.

“A lot of parents were calling because their kids said, ‘This sounds like something I want to be involved in,'” he said, adding that he’s still getting emails regularly from parents wanting to sign up their teens, even with enrollment ended.

When 14-year-old Audrey first heard her mother say there was a vaccine trial starting for kids at a nearby Cincinnati hospital, she immediately raised her hand. Her 12-year-old brother, Sam, wasn’t quite so quick to volunteer.

But after talking it through together with their mother, Rachel, a nurse, they both decided to get their first shots of the Pfizer Inc.-BioNtech SE vaccine at the same time in December. About two weeks later, the siblings got their second dose. Now, they’re among about 2,300 teens administered shots in the trial who are anxiously waiting to see if they received the vaccine or a placebo.

Sam is certain he got the vaccine because he had a headache and chills after the second shot, known side effects for adults. Audrey, meanwhile, says she’s jealous of her brother and curious about her own vaccination.

The siblings won’t know for sure which they got until the shot is approved for use in their age group, according to Frenck. At that point, the result will be unblinded and those who received the placebo will have the opportunity to get the vaccine.

In the meantime, the siblings – whose mother has asked their their last name be withheld – have both discussed being in the trial with friends, some of whom said they’d like to be in a test as well.

There have been some complications in dealing with parents and teens, according to Frenck. In some cases, parents backed out after he explained that their children may be getting a placebo.

One of the first steps in the enrollment process is for the parents to sign a consent form, and the child to sign what Frenck described as an “assent” form. In a few cases, teens have come in and decided it wasn’t for them. “Parents look at them and say ‘really?’ But if the parents say yes and the adolescent says no, the adolescent wins,” he said.

While Pfizer had around 40,000 in its adult studies, it is testing a far smaller number in its trial in children: just 2,300.

Frenck says there’s a good reason for that. In children, researchers are undertaking what Frenck describes as an “immunological bridging study” that compares the immune response found in children with that already proven to work in the larger study in adults.

If they match up, and the shot is found to be safe in children – and Frenck says there’s no indication yet that it isn’t – the study will be a success.