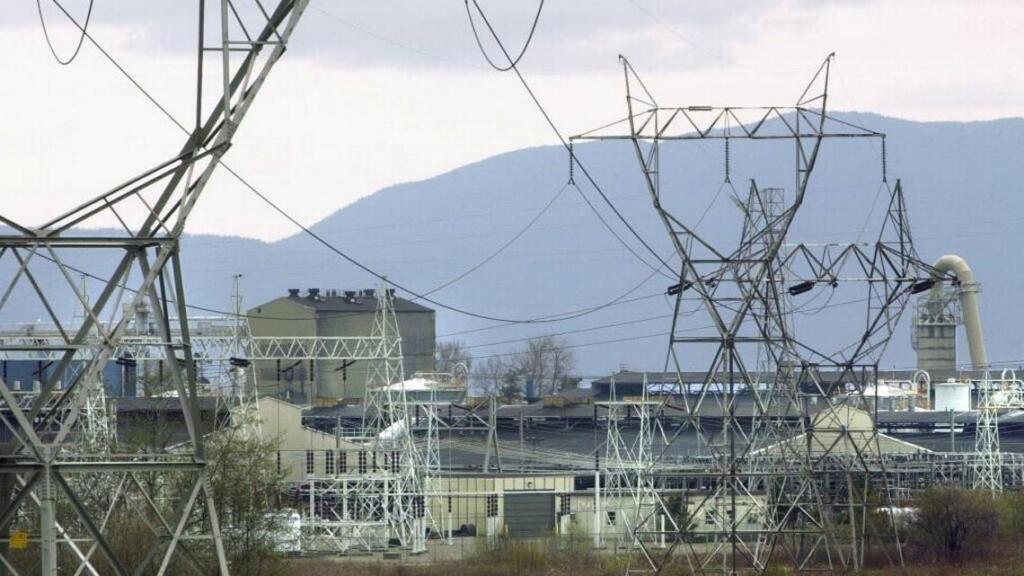

SEATTLE — The hard-fought battle to reopen a “green” aluminum plant near Bellingham came to a halt this month. But it may not be the end.

Blue Wolf Capital, a private equity firm based in New York, pulled out of the project, citing electricity rates that are too high to make the project profitable. The investor had hoped federal subsidies through the Inflation Reduction Act would help close the gap between market-rate power and the rate needed to make aluminum production fruitful.

There still might be an opportunity to revive the plant. A new Department of Defense report to Congress says production of aluminum, specifically high-purity aluminum, may need a boost from the Defense Production Act. The DPA gives the president the power to order companies to produce goods for national defense.

Aluminum is used in commercial and military aircraft, and staples in the transition away from fossil fuels such as solar panels, wind turbines and electric cars. It’s an energy-intensive industry. Electricity makes up about 40% of production costs in aluminum smelters, according to a federal report.

The Bonneville Power Administration sells power at cost to so-called Northwest preference customers: public utility districts, municipalities and electric cooperatives. It also sells surplus power at market prices, which has become more lucrative during the past year. Through the years, those market sales have helped defray expenses and limit the size of BPA rate increases imposed on consumer utilities.

For half a century, the BPA provided low-cost electricity to the Intalco aluminum smelter in Ferndale as a direct industrial customer. But that era ended when Alcoa terminated the Intalco agreement before mothballing the facility in 2020.

Efforts to fire the plant back up picked up speed in the summer of 2021.

But Blue Wolf ended negotiations with BPA last week, after the agency refused to budge on its offer of market-rate electricity, said Josh Gotbaum, Blue Wolf senior adviser. That’s much more than the agency’s other preference customers are paying, he said, and credits from the Inflation Reduction Act weren’t going to make up the difference.

“The fundamental requirement for reopening was getting affordable, clean power of a certain amount,” said Jason Walsh, executive director of the BlueGreen Alliance, a clean-industry advocacy group. “And BPA never changed its counteroffer.”

Bonneville Power also said it could offer only a fraction of the 400 megawatts of electricity that Blue Wolf said it needed to take over the plant, Gotbaum said.

Most aluminum production in the U.S. and abroad relies on fossil fuels, while emitting a significant amount during production. The Ferndale smelter, for example, emitted nearly 50 tons of perfluorocarbons in 2020 before curtailing production, Inside Climate News reported.

The Intalco plant would’ve been fueled by hydropower and, eventually solar and wind. And the Northwest Clean Air Agency, Intalco, and Blue Wolf helped develop a plan to install new emissions controls in an aim to meet air quality standards and reduce emissions.

Efforts to reopen the smelter garnered the support of Gov. Jay Inslee, state lawmakers, Washington’s congressional delegation, the machinists union, and some environmental groups as a means of ensuring national security, local jobs and materials for a decarbonized future.

The state Legislature secured $10 million in the capital budget for the plant’s emission controls and other renovations during the last session. And in April, state lawmakers sent a letter urging BPA to reach a deal to reopen the only aluminum plant in the western U.S.

“It’s just so disappointing to see a project like this fall through,” said Annie Sartor, who leads the aluminum campaign at Industrious Labs, an advocacy group working to decarbonize industry. “The union and the workers want to see it. The climate community wants to see it. The Washington state government has invested to make this happen.”

But is this the end for the Ferndale plant?

In 1993, the U.S. had 22 active aluminum smelters. Now there are five.

Restarting aluminum plants has been cost-prohibitive without big investments from the private sector. For example, it could cost around $175 million to fire up the Ferndale smelter again.

New processing technologies with lower upfront costs are available for the production of high-purity aluminum, according to the report from the Department of Defense.

The report says aluminum production is critical to national defense, and due to the disruption to the energy market, domestic production may not sustain sufficient levels without support from the Defense Production Act.

“We urge the administration to take the conclusions of this report seriously and use the Defense Production Act to rebuild the aluminum industry and bring back union jobs to safely meet our defense needs,” Sen. Maria Cantwell and Representatives Rick Larsen and Suzan DelBene said in a joint statement. “Failing to do so would threaten our critical infrastructure and defense capabilities and risk losing more manufacturing jobs.”

The report was mandated by a provision included in the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act by Cantwell, Larsen and DelBene.

When Alcoa closed the plant in 2020, about 700 residents of Whatcom County and surrounding areas who worked at the plant were put out of work. Among them was Ferndale City Councilmember Paul Shuey, an Intalco employee of 16 years.

“It was a great family-wage job,” he said. “It was a great place to learn a bunch of things and increase your pay. And it meant stability — for me, for people here in Ferndale.”

At the plant, he worked toward his GED and learned how to work in the rod shop, cast house and emissions control. Now he’s cashed out his 401(k), and is working long hours in a construction job to make his mortgage.

About 90% of the 700 workers laid off in 2020 say they’d come back to work there, said Luke Ackerson, business representative of the local branch of the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers.

“It’s part of who Ferndale is,” Shuey said. “That’s one of the things that Ferndale took pride in, was making aluminum.”

Material from The Seattle Times archives is included in this report.