ORLANDO, Fla. — When Kerri Donaldson Hanna looks at the full moon she sees a future full of opportunity.

“I see so much possibility. Humans have put their feet there, looked back at Earth, and saw it as that object in the sky,” said Hanna, a planetary geologist at the University of Central Florida. “I see it as a geographically interesting place. It holds a lot of what’s possible for our future. We’ve been there, but what else can we do?”

Hanna and a research team of UCF students are working to print a map of possibilities by creating spectral instruments for a NASA satellite capable of scanning and producing high-resolution maps of water on the moon.

In 2019, NASA selected the Lunar Trailblazer mission, along with three other proposed missions, for further study under its Small Innovative Missions for Planetary Exploration program. The following year, NASA approved Hanna’s plans for spectral mapping for a 2025 launch. Although Trailblazer could launch as soon as next year, Hanna said, “I would be shocked if in the next month or two, we don’t find out that we’re going sooner.”

Her confidence is fueled by how busy Orlando skies will be in the next couple of years with traffic driven by NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services initiative — which aims to put several landers on the moon — as well as several other scheduled NASA projects.

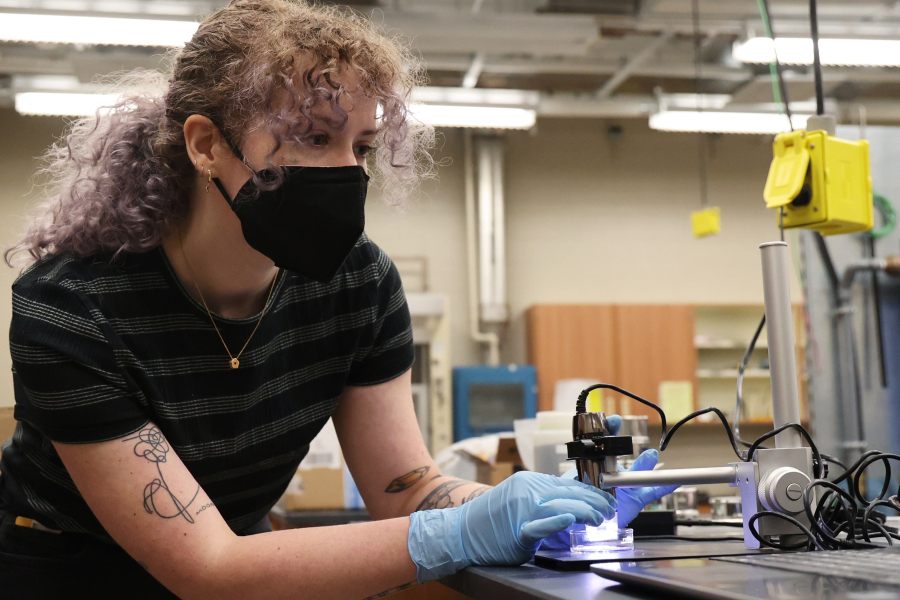

For now, Hanna and the team are preparing for the mission by using the spectral camera to study how ice, water-ice, and hydroxyl interact with lunar regolith. While they don’t have access to real moon dirt, they’re doing just fine using a simulant soil created by UCF’s Exolith Lab, which specializes in creating imitation alien soil for experiments and equipment tests around the world.

The importance of finding water on the moon cannot be stressed enough. Its abundance would create an element of ease for explorers and land developers who would gladly not have to rely on shipping tons of life-saving and rocket-fuel-producing liquid via rocket ship. Any sites Trailblazer confirms to have water will most likely become target locations for NASA’s Artemis missions, which seek to return humans to the moon, including the first woman to the surface.

Water has been long suspected to be on the gray surface of the moon since 1999 when the Lunar Prospector probe first detected a high level of hydrogen in the north and south poles. But those results are more ambiguous regarding water’s presence than factual, Hanna explained.

“It’s really a large spatial footprint, meaning it averages its measurements out over an area of 100 kilometers by 100 kilometers. And somewhere within that 100 kilometers, we could just have a lot of hydrogen, or maybe you have small amounts of hydrogen mixed out over the entire footprint. It’s hard just to know for sure,” she said.

Most lunar scientists agree that water-ice exists in the permanent shadows of craters safe from the sun’s evaporating rays. But there are few actual detections of frozen water. Lots of remote sensing measurements have suggested where water should be, such as surface-temperature maps, but Hanna is hoping Trailblazer can end the speculation and unearth facts hidden beneath the surface — or on the surface.

Trailblazer will scan geographical areas of interest as low as crater floors and as high as mountain peaks. One of the key features Hanna and the team are designing is an electron microscopy scanner to characterize depictions of the surface at the microscopic level.

Previous datasets, such as the Moon Mineralogy Mapper collected by India’s Chandrayaan-1, lacked power enough to differentiate among molecules of water-ice, molecular water, and hydroxyl. Trailblazer should be able to measure all the way down to 3.6 microns, Hanna said, making the satellite uniquely qualified to distinguish any of the three.

One of Hanna’s researchers, Autumn Shackelford, a 24-year-old graduate student, is wetting lunar regolith, freezing it, and observing what sorts of structural, spectral signature changes the material shows. The point is to understand exactly what they’re looking for. While Trailblazer circumnavigates the moon it will be scanning the topography. Hanna and Shackelford’s research should give the team a heads up of what kind of spectral signatures or geography may yield the best locations to find water.

Shackelford’s name is serendipitously suited for her research position, as the Moon’s Shackleton Crater in the South Pole was the first place water was originally detected. Since then, Shackleton Crater has been targeted by space agencies around the world as the most likely first location for colonization.

The coincidence isn’t lost on her, but Shackelford is focused on what her research can tell us about the moon.

“I didn’t think about the moon much at all before I started grad school, but it’s much more interesting than I ever could have thought,” she said.