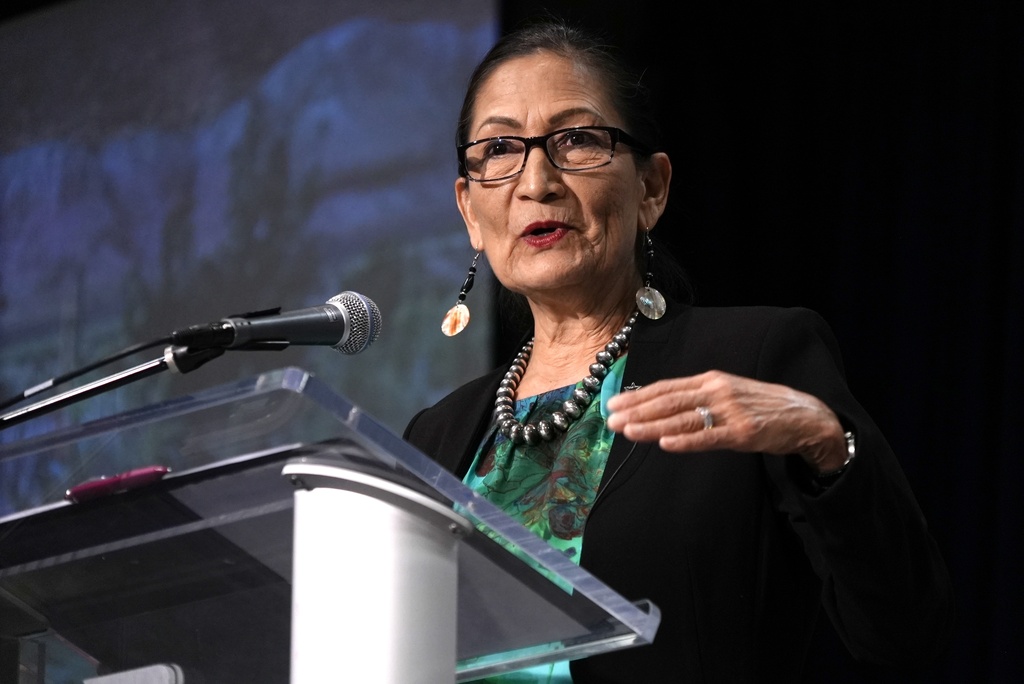

TULALIP — U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland raised her hands as Hiahl-tsa’s “Welcome Song” echoed throughout the wood-paneled walls and century-old tree trunks of the Tulalip Tribes’ gathering hall Sunday.

Songs like these “were things that our people had always had, and the boarding school era tried to take away,” said Glen Gobin, a longtime Tulalip tribal leader and former board member.

Just months after the Interior Department released its first investigative report on 408 federally supported boarding schools, detailing how they were used to separate Indigenous children as young as 4 from their families and communities, Haaland embarked on a yearlong “Road to Healing” tour.

Sunday was her first appearance in Washington state on the journey. It was her sixth stop.

“Federal Indian boarding school policies have touched every Indigenous person I know,” said Haaland, an enrolled citizen of the Laguna Pueblo tribe. “Some are survivors, some are descendants, but we all carry this painful legacy in our hearts. … My ancestors and many of yours endured the horrors of Indian boarding school assimilation policies carried out by the same department that I now lead.”

In the schools, children were physically punished for speaking their native language, practicing their culture or trying to escape. According to the May 2022 report, school officials put children in solitary confinement, slapped and flogged them, withheld food and sometimes forced older kids to punish the younger ones.

The goal — written in federal laws, court rulings and congressional testimony — was cultural assimilation and territorial dispossession.

Still healing

There were at least 15 federally operated or funded boarding schools in Washington: up and down the Interstate 5 corridor, on the coast, dotted through the arid grasslands of the eastern parts of the state. Many of them were on present-day tribal land.

More than a hundred survivors and descendants of survivors of Native American boarding schools across the West packed the gathering hall Sunday. The people, from Lummi, Suquamish, Yakama and beyond, shared stories of students’ mouths being washed out with soap until they cracked and bled for speaking their native language, of school leaders whipping them with ropes and belts, of sexual abuse, and of intentionally breaking the rules so they would be thrown out of school and freed from the abuse.

The systematic efforts to assimilate and eradicate Native people in many places began with religious organizations, as missionaries planted churches and religious schools on reservations.

But “this has never been about religion,” said Matthew War Bonnet, Sicangu Lakota, a survivor of St. Francis Indian School in South Dakota and a resident of Snohomish. “It’s been about people abusing children; men abusing children physically, emotionally and mentally. Many kids I went to school with grew up to be abusers of themselves, abusers of their families, abusers of their communities until they just quit.”

War Bonnet, 77, brought a rope, a belt and leather straps to the gathering hall Sunday to explain what he and his peers had endured. That abuse was something he knew for 10 months of the year for his entire childhood. Students like War Bonnet were only permitted to see their families for a few months during their boarding school years.

Virginia Bill’s mother was a member of the Swinomish and Upper Skagit Tribes. She and her siblings were taken from Bow Hill and placed in boarding schools, Bill said during the listening session Sunday. The youngest was 5.

Some were taken to Tulalip and forbidden from talking to their sisters. The family bonds were broken.

“When she got here to Tulalip, she did talk of having to be marched everywhere,” Bill said about her mother. “She talked about that bell that would ring. I think it was in the 1980s we were brought here to a ceremony to commemorate this bell. I found mom sitting alone by herself. … She said, Thank God it’s silenced.”

The bell dictated every hour of students’ days.

Today, there’s no plaque, there are no markers to recognize what students endured at the Tulalip boarding school, Bill said.

“I thought I might have been the only survivor of a boarding school, but it’s so good to hear and know that we’re all the same,” said Ernestine Lane, a Lummi Nation elder. “We’re not healed yet. I’m 99 years old and I’m still healing yet.”

On Tulalip Bay, all that physically remains of the boarding school is the dining hall and rubble of an old concrete jail on the shore.

Dark history

A French Catholic priest started a mission school in Tulalip in 1857. He forced children as young as 7 into unpaid manual labor. They planted 10 acres of potatoes, peas and other vegetables. They logged land to create a cemetery in 1869.

The Rev. Eugene Casimir Chirouse oversaw a girls school too, founded about 10 years later by the Sisters of Charity of Providence. The nuns’ diaries recorded diseases brought by white settlers that spread through the small dorm of 60 girls.

Even after the federal government inherited the school campus at Tulalip in the early 1900s, students were still required to attend church and religious courses.

The manual labor continued, too. Schedules dictated by the federal government outlined that boys would spend half of each day clearing land and chopping wood for heat. Girls served meals to their peers and worked in the hospital.

Meanwhile, abuse ran rampant. Students of the Tulalip Indian School have recalled seeing other children crawling after the school officials whipped them for attempting to run away. Others remember their relatives spending time in the small concrete jail on the bayshore for speaking just a few words of their native language of Lushootseed.

Government officials ripped thousands of Indigenous children from their homes across the Pacific Northwest and brought them to the Tulalip Indian School every year until it closed in 1932. Meanwhile, some Tulalip children were taken to schools as far away as Oregon and Nevada.

Tribal nations did not gain the right to run their own schools until 1975, and parents could not deny their children’s placement in off-reservation schools until the Indian Child Welfare Act passed in 1978.

Time to listen

These schools have touched at least one generation of every Native American family. Today, the intergenerational trauma persists. In a survey of 22,602 First Nations people, over 70% of respondents said they felt their grandparents’ attendance at a boarding school negatively affected their parents’ upbringing.

Deborah Parker, a citizen of the Tulalip Tribes and chief executive of the boarding school healing coalition, said it was a deep honor for Haaland to visit and listen, but people are still waiting for apologies.

“It’s time to listen to America’s dark past,” Parker said. “And to really bring the atrocities to light and to find some healing and justice.”

To fully express and understand the impacts of the federal policy of Native American child removal, Parker’s organization is advocating for a congressional commission to find and analyze the records from the boarding schools, and to bring together boarding school survivors with experts in education and health.

The organization will soon release a report detailing more than 500 U.S. boarding schools that severed Indigenous children from their families in the name of assimilation. That’s more than 100 more than were identified in the Interior’s report.

Interior’s report was a key first step in a long-awaited reckoning with the federal government’s wrongs to Native people. The 106-page report identified 53 marked or unmarked graveyards where students were buried. The initial investigation found at least 500 Indigenous children died in about 19 schools across the country.

“We as Indian people have never been apologized to,” said Tulalip elder Don Hatch.

Next steps include identifying additional burial sites across the Native American boarding school system, and trying to determine the total amount of federal funding that was dedicated to those boarding schools, said Bryan Newland, assistant secretary of the interior.

Tulalip drummers and singers at the gathering hall wore orange ribbon skirts, sweaters adorned with cedar paddles and T-shirts calling attention to the legacy of boarding schools. They bookended the event with songs shared by their relatives. Their voices bellowed. Drums rattled the room.

“We’re still here,” Parker said. “We’re not going anywhere and we’re going to speak our language. We’re going to bring back that peace and beauty that exists within our culture and our spirit and our bloodlines.”

If you are a boarding school survivor or a descendant, resources are available from the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition at: boardingschoolhealing.org.