SEATTLE — When safety investigator Rose Kracht arrived at Amazon’s warehouse in DuPont, Washington, just hours after she had left the night before, she was blocked.

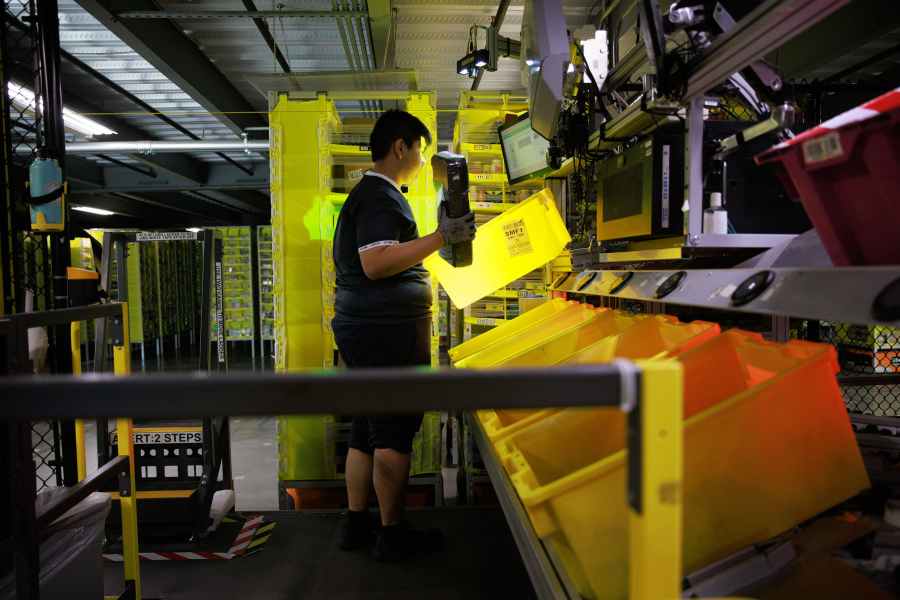

Kracht, an inspector with Washington’s Department of Labor and Industries who was following up on worker complaints, came armed with heart-rate monitors, wearable sensors, a GoPro camera and a digital survey, prepared to ask employees what it was like to work at Amazon. Inside, Amazon employees unloaded trailers, packed boxes and moved thousands of items through the 1.1 million square foot facility. The roughly 1,000 people employed there worked among conveyor belts, robotic arms and autonomous robots moving customer orders from one station to the next.

But that morning in August 2021, Chris Murphy, Amazon’s workplace health and safety manager for the suburban Tacoma warehouse, turned Kracht and her team away, Kracht later reported.

It wasn’t the first time Amazon blocked inspectors. But the act teed up a high-stakes legal battle between Washington’s workplace safety regulators and one of the state’s largest employers, a fight now playing out before a state board that adjudicates appeals of L&I decisions.

L&I claims Amazon created an unsafe work environment in three Washington warehouses, and has fined Amazon four times for failing to keep workers safe. After a series of appeals by Amazon, the department and the company went to trial in July, kicking off a weekslong contest that could determine the future of work at Amazon. If L&I prevails, Amazon will have to make changes to its operations at the department’s behest. If the court rules for Amazon, state regulators’ hands may be tied going forward.

Amazon says it’s already improving safety at its warehouses — it points to new training, equipment and other investments — but L&I inspectors worry about the risk of injury each time an Amazon employee clocks in. It’s a concern shared by federal workplace safety regulators, the Department of Justice and some in the U.S. Senate, all of which are investigating Amazon’s warehouses.

While the injury rate at Amazon warehouses has declined, the extent of that decline and how the company compares with the rest of the industry is hotly contested. A coalition of labor unions that analyzed 2022 regulatory data found the overall injury rate at Amazon was 7 injuries per 100 workers in 2022, 70% higher than the rate at non-Amazon warehouses.

Amazon disputes that assertion, and says the unions’ comparison to others in the industry is flawed. Amazon found in its own analysis, which used a different injury rate measure, that rates at U.S. facilities fell to 6.7 injuries per 200,000 working hours in 2022.

The faceoff in Washington serves as an early test of Amazon’s authority to shape work within its warehouses, and the culmination of an investigation three years in the making.

Bodies in repetitive motion

L&I opened an inspection of Amazon’s DuPont facility in November 2020, after a report from news outlet Reveal painted a grim picture of the working conditions at Amazon’s warehouses. Based on injury logs Amazon filed with the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the facility had the highest injury rate of any of Amazon’s U.S. warehouses.

The next month, L&I received an anonymous complaint from an employee there who alleged the facility had exposed cables, sharp-edged poles and wobbly pallets stacked too high. There was battery corrosion and fluid leaks, the employee wrote. Eye protection provided workers was not certified, the complaint continued. And the company was not informing injured workers of their right to see a doctor.

That and dozens of similar complaints were among the L&I documents obtained by The Seattle Times through a public records request. Those records, along with hundreds of pages of documents produced by L&I and Amazon during the ongoing court proceedings, provide new insights into life inside the online retailer’s warehouses as its distribution operation doubled in size during the COVID-19 pandemic.

When the pandemic supercharged online shopping, the demands on Amazon’s fulfillment network skyrocketed. As it built warehouses and hired workers, the company also faced escalating allegations that the facilities that kept its online marketplace humming weren’t safe.

Delivery drivers sued Amazon for setting unreasonable expectations, sometimes demanding so many drop-offs that drivers have to pee in bottles while on their routes. Warehouse workers accused the company of forcing them to move too fast, ignoring the company’s own guidelines and failing to help when they were injured. Some started to unionize, hoping to improve working conditions.

Investigators at the DuPont facility found Amazon had not provided the tools, equipment and practices to protect workers, according to reports from the ergonomists — medical experts who study safety and efficiency in workplaces — who toured the warehouse over two days.

The reports chronicled a litany of problematic practices: Workers pulled cages that weighed 600 to 700 pounds. Some said they had 12 seconds to move an item from one process to the next. Those items were not supposed to weigh more than 50 pounds, but some clocked in at 70. Amazon did not allow employees to lift in teams.

“If the pace of work is not reduced, or breaks are not provided, or over-time is not discontinued, serious injuries can occur,” Drs. David Rempel and Robert Harrison, occupational medicine physicians retained by L&I, said in a report.

Serious injuries aren’t just “broken bones or amputations,” Kracht, the lead inspector, wrote. “When an employee states their back is broke from physically lifting hundreds of items per hour … we can conclude this is serious physical harm.”

The regulators worried employees would develop musculoskeletal disorders — strains, sprains or tears caused by repetitive motions. In DuPont, nearly a third of Amazon workers who developed MSDs were off the job for at least 100 days, ergonomist Richard Goggins found in an analysis of data from 2006 to 2018.

Goggins, an ergonomist who has worked with L&I since 1995, was a part of the team that inspected Amazon’s DuPont warehouse in 2020. In July, at the start of the trial before the state Board of Industrial Insurance Appeals, Goggins told the judge he prefers to observe workers for long periods of time so they forget about him and slip back to their normal habits. But in DuPont, the line feeding packages to the worker he was watching stopped abruptly, even as workers at other stations continued to handle packages.

Maureen Lynch Vogel, an Amazon spokesperson, said it is normal for there to be a pause in workflow and fluctuations in items coming down the line. Any allegations of Amazon interfering with the inspection are “mischaracterizations” and a “distraction from what is actually at issue,” she added.

Over the months that followed, those ergonomists inspected two other Seattle-area Amazon warehouses, investigating DuPont twice. There were differences among the facilities, but L&I found workers performing dangerously repetitive motions in each. In Amazon’s Kent, Washington, warehouse, a 1.1 million square foot facility that usually employs 2,600 people, the department found the fast pace of work was directly connected to the high injury rate.

Inspectors found the long hours at Amazon meant the equations they rely on to calculate the injury risk were likely an underestimate. Those equations assume an 8-hour workday, while Amazon ran 10-hour shifts, and the risk of injury increases as workers tire.

“The danger zone”

Rempel, one of the physicians, told the court he worried about Amazon’s use of “Taylorism,” a labor philosophy developed in the late 19th century used in factories and manufacturing. Following Taylorism, companies break jobs into specialized, repetitive tasks to improve efficiency.

An Amazon spokesperson told The Seattle Times workers can take breaks as needed and managers are told to prioritize safety and quality over speed. The company says it only sets goals for its lowest-performing employees, and those goals are reasonable.

But Rempel said the system pitted workers against one another, forcing them to compete to move the fastest. Amazon was creating a “psychosocial risk,” he said, and increasing workers’ stress and chance of injury on the job.

While the inspections continued, the department received anonymous complaints from workers inside warehouses around the state, complaints obtained by The Seattle Times. One tipster said conveyor belts lacked emergency stops, meaning workers’ hands were always “in the danger zone.” Vogel, the Amazon spokesperson, said it would be “against policy” to have employees working with broken or malfunctioning equipment.

Another employee said walkways were blocked, while another said workers would operate machines without training. Two reported high temperatures making workers feel sick.

“The work environment is both unsafe and toxic,” one worker from Spokane wrote to L&I. “At Amazon, they ask that you put a round peg in a square hole. And if it doesn’t fit … it’s somehow your fault.”

“It is not the safety of the employees that matters,” the worker continued, “but getting the product out.”

Amazon disputes practically all of L&I’s claims. The company constantly looks for ways to improve and has seen a decrease in injuries over the past several years, Amazon representatives wrote in court documents.

At its DuPont warehouse, injury rates declined in one year from 24 injuries per 100 workers to 14 injuries per 100 workers, Amazon said.

In December 2020, just after L&I first visited the DuPont warehouse, Amazon hired a specialist to monitor employees and equipment for ways to improve safety, according to court documents. In Kent, Amazon had 19 employees as part of its health and safety team.

Amazon lowered some conveyors, redesigned ladder railings and added a small platform to help workers access high shelves without awkward reaches. It was “piloting” new ways to make work safer, Vincent Racco, a senior workplace health and safety risk manager at Amazon, said in court papers. But the “evaluation process is extensive and takes time,” Racco said. If not done carefully, he asserted, new equipment could introduce new risks.

“This is not a matter of an employer refusing to guard a frequently used buzz saw or otherwise rejecting fall protection for workers at dangerous heights,” Amazon wrote in court records. “This is the complex world of ergonomics.”

Aside from providing new equipment, the company contends, Amazon trains new hires at a “safety school” they then repeat annually. Employees attend 10-minute learning sessions monthly, and managers guide stretching each shift.

While L&I argues Amazon must make changes to prevent any further injuries, Amazon says it should be allowed to keep moving at its own pace. The injuries in question, “which Amazon denies entirely,” are “based on repetitive motion and slow to progress,” Amazon wrote in court records.

Amazon is implementing its plan to improve safety and decrease injuries “through those who know best — the internal ergonomics experts,” the company wrote.

An “upside down” approach?

L&I inspectors allege that Amazon hadn’t acted on its plan and that it had put the blame on workers rather than a system that was “hazardous by design.”

After a visit to the Kent warehouse, inspectors reported Amazon had a “well-designed” ergonomics plan but “it does not appear that management … followed this standard.”

Despite a focus on training workers on ergonomics, most employees L&I interviewed during its inspection of a facility in Sumner did not know what “ergonomics” means. Murphy, the workplace health and safety manager at the DuPont warehouse, said in an interview with L&I that he did not have any in-depth knowledge of the subject.

Amazon’s plan called for employees to engage their core while lifting, shake out their hands and arms and take “microbreaks” throughout their shift. But, employees told L&I, when the computer at their work station prompts a stretching break, minutes spent stretching can count as “time off task.” Too much “time off task” can lead to repercussions, including termination in some cases.

Lynch, the Amazon spokesperson, said workers would not be penalized for taking informal breaks to stretch at their workstations. “If that did ever occur, we’d investigate the situation and address it directly with the manager,” she added.

Employees were trained to lift within the “power zone,” a hypothetical box that would reduce the risk of injury, but many of Amazon’s workstations were designed in a way that made that impossible, Rempel told the court in the first week of trial.

In more than 30 years as an ergonomist, Rempel said he found that workers switch back to innate techniques when they’re tired. No matter the training, the fast pace of work and long hours tires workers and increases the risk of injury, he said.

Goggins argued Amazon’s approach to mitigating risk was “upside down.” It focused on stretching and training, rather than changes to the equipment, pace of work and the design of job tasks. When Amazon implemented engineering controls, it skipped the riskiest areas, Goggins and Kracht said.

In Kent, Amazon had given employees wearable devices that vibrate when they strike an awkward posture. But the pace of work didn’t slow, so workers didn’t have the time to adjust their stances, Goggins wrote in court records. That device, he continued, became “just another way of making employees believe it is their fault” when they struggled to work safely and keep up the pace.

Years to go

In May 2022, the Industrial Insurance Appeals Board ordered Amazon to make changes to its Kent warehouse, denying the company’s request to wait until its appeals were resolved. The board is an administrative court that adjudicates contested L&I citations. Its decisions can then be appealed to state or federal courts.

In similar cases involving other Amazon warehouses, the board denied Amazon’s requests to delay fixes demanded by L&I after finding that employees were still at risk of injury. But that May, the board denied Amazon’s request for a different reason: Amazon failed to notify workers of the L&I citation, violating state law.

Amazon later appealed the board’s decision to federal court, arguing the department was forcing the company to make “disruptive” changes before it had proved its allegations. A federal judge in Seattle ruled against Amazon in March.

Nearly three years since the first inspection, the trial between Amazon and L&I that began in July is likely to last through September.

In opening statements July 24, attorneys for both parties focused on how L&I measures risk of injury. Jeffrey Youmans, an attorney with Davis Wright Tremaine representing Amazon, accused L&I of using techniques that don’t factor in the variability of work at Amazon — and using those tools incorrectly.

Furst, the attorney representing the state, accused Amazon of trying to bypass the law by claiming the tools weren’t fit for “the new modern type of workplace we have invented.”

Already anticipating an appeal regardless of the outcome, Furst wrote in court records leading up to trial that the case could take years more.