YAKIMA — On a spring day in 1889, several Catholic nuns, priests and other residents of the railroad town of North Yakima watched as Indigenous children gathered near a new school building near St. Joseph’s Catholic Church.

It was April and the Yakama, Kittitas and Simcoe children were among a total of 19 enrolled at the boarding school for Native students, which faced Naches Avenue between “C” and “D” streets. The school was part of St. Joseph’s Academy, which the Sisters of Providence had run since it opened in nearby Yakima City.

“The event was a colorful affair, the youngsters dressed in the regalia of their tribes and staging a procession which attracted much attention of the local citizenry,” Ellis Lucia wrote in “Magic Valley: The Story of St. Joseph Academy and the Blossoming of Yakima,” an electronic publication by Providence Archives in Seattle.

Though enrollment grew quickly, the boarding school for Native children at St. Joseph’s Academy closed less than a decade later, when the nuns learned in July 1896 that the U.S. Department of the Interior would no longer subsidize private sectarian schools. The federal government had been paying for education of 50 Native students at the school, where enrollment reached 87 in the fall of 1891.

The issue of Native boarding schools has received extensive international attention and media coverage in the year since the U.S. Department of the Interior released the first volume of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report in May 2022. But specific information about many boarding schools, who attended them and school burial sites remains elusive because records are scattered, lost or inaccessible.

Yakima County had two schools in the report: Fort Simcoe near White Swan, which operated from 1861 to 1920, and the North Yakima school. While records are limited on both, the North Yakima boarding school operated for a much shorter period, making information even scarcer.

Descendants, other tribal citizens and researchers have pushed for more transparency from government and religious officials. In early May, a group called Catholic Truth and Healing released a list of Native boarding schools affiliated with the Catholic Church. It provides details about 87 Catholic-run Native boarding schools in 22 states and appears on a new website compiled and refined by a group of archivists, historians, concerned Catholics and tribal citizens.

They created it to share information for survivors of Native boarding schools, their descendants and tribal nations, according to a news release.

“Basic information, such as how many Catholic-run Native American boarding schools operated in the United States and where they were located is critical information that must be known for the truth-telling and the reconciliatory process to take place,” said Jaime Arsenault, tribal historic preservation officer for the White Earth Band of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe.

Many mysteries

In just one example of the multiple challenges researchers and tribal citizens face in learning more about boarding schools and who attended them, finding any publicly accessible photos of the boarding school for Native children in North Yakima is challenging, though maps exist.

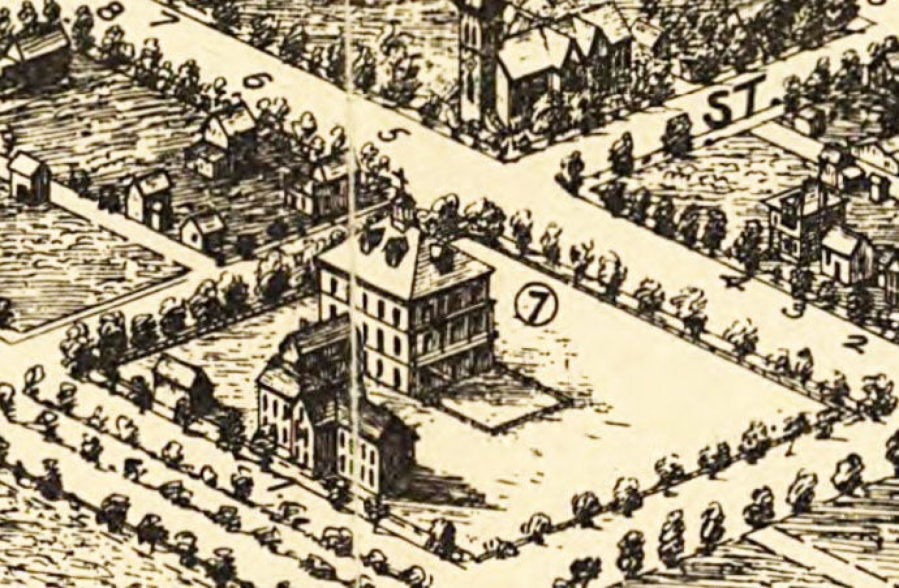

A shadowy 1905 photo from the Relander Collection in the Yakima Memory digital archives shows the main St. Joseph’s Academy building that stood near the northeast corner at the intersection of North Fourth Street and what was then “C” Street (now Lincoln Avenue). Sanborn Fire Insurance maps show the boarding school for Native students in another building east of the main structure, facing Naches Avenue.

There is no information about the photo, which appears to have been taken looking to the north. A Spike & Arnold map from 1889 shows the main St. Joseph’s Academy with two dormer windows on its east and west facades and one dormer window on the north and south facades; only one dormer window is visible on the facade in the 1905 photo and the ridgeline can be seen in the background.

Another building in the photo, to the right of the main academy, could be the boarding school for Native children. Sanborn Insurance maps from June 1897 describe the boarding school as a “vacant building.” It was still standing in October 1905 and being used then for extra classrooms, according to Sanborn maps, but is gone from Sanborn maps by May 1909.

The school had to close because of finances, Sister Anna Clare Duggar wrote in “St. Joseph’s Academy, Yakima, Washington 1875-1950”, which was published in 1951. “Since this mission was too poor to continue to educate and care for the Indians without government aid, the school had to be closed,” she wrote.

Priests at the St. Joseph Ahtanum Mission had discussed adding a boarding school for Native students even before the first three nuns traveled from Vancouver in November 1875 to open a school in Yakima City, today’s Union Gap.

“I will try with the Bishop for his material help in our contemplated Indian School as soon as I have the opportunity, as you kindly counsel me to do,” the Rev. Joseph Caruana of the Society of Jesus, also known as the Jesuits, wrote in a May 1875 letter to Sister Praxede. “Yes, I too, principally wish to see the school going on among my cherished Indians, but at the same time I could not abandon the poor white children.”

After moving their school from Yakima City to North Yakima in 1887, in December 1888 “it was decided to build a school for the Indians separate from the Academy,” Duggar wrote. “The work was to be started in February and the building ready for use by the twenty-second of April.”

The main St. Joseph’s Academy building stood on the same block near the Native boarding school, to the west of it, and was barely a year old. That three-story brick structure, 60 feet square and capped by a small belfry, was completed in early March 1888. The boarding school for Native children was smaller, with room for about 40 students.

“The project wasn’t a popular one, as many people didn’t like the idea of white and Indian youngsters mixing together on the same grounds,” Lucia wrote in “Magic Valley.”

But demand from potential students was high, according to Duggar. “The enrollment in the Indian school in April was 19 and the sisters were obliged to refuse a great number because of lack of room,” she wrote. “There were so many applications that it was decided to build an additional wing. This was to be used for the housing of Indian boys.

“In this way the boys and the girls would each have a wing of the building to themselves,” Duggar said. “The school now had an enrollment of sixty pupils.”

Nuns taught the girls and Jesuit brothers taught the boys, according to a Northwest Catholic article about the Catholic Truth & Healing list. A number of the Native children at the school in North Yakima came from Kittitas County. An August 1889 article in the Yakima Herald noted that in a story about the school.

“On Monday Father Garrand and a couple of the sisters escorted twenty-two of the scholars to their homes in Kittitas County,” it said. “The Indian school maintained at Yakima by the Catholics closed on Saturday last for a vacation of two months.”

Though they weren’t at the boarding school year-round, which was also the situation at the Fort Simcoe boarding school, the children “found school life hard and the sisters found it hard to keep track of them,” Duggar wrote. Native families commonly took part in traditional gathering, hunting and fishing, and moved seasonally.

“The nomadic life they had been accustomed to living had not prepared them for sitting in classrooms for several hours a day; such a program was nothing less than torture to them,” she wrote. “They would simply walk off and in a few days return without a word of explanation.”

When possible, the nuns took the Native and white children outside, to work in small garden plots near the school buildings and on picnics and walks. Tragedy resulted from one outing in the spring of 1892.

“On Monday last a sudden and alarming sickness took possession of five of the boys of the Indian training school. Dr. W.G. Coe was summoned and found two of the children in convulsions,” the Yakima Herald reported on March 31, 1892. One of the sisters had taken the children for a walk and some ate wild parsnips, Duggar wrote.

“Before they could be gotten home or help brought to them, two died,” she wrote. “Three more died during the night.”

Their names are unknown. Neither the newspaper nor Duggar included who they were, their ages or where their families lived.

The future

A federal inspector toured the boarding school in the spring of 1893 to “examine the condition of the school, the studies taught, the meals served, and everything that pertained to the care of the Indian children. He came back for a surprise visit three months later “to find things in the same condition as on his previous one,” Duggar wrote.

“The first time I came I thought that you had made special preparations for me but now I see that you always have things up to date-perfect,” she wrote in quoting the inspector.

When the school closed in June 1896, there was no indication the government contract would not be renewed. But school and church officials learned in July that no more financial support would be coming from the federal government for the boarding school for Native children. St. Joseph’s Academy faced heavy debt and lost most of its students.

“There were very few day-pupils and only three boarders,” according to Duggar.

Thanks to a supporter who paid off the debt, and the nuns who recruited more students, the academy stayed open. It continued to operate until 1969.

Current day

In 1978, the Naches House apartment building was constructed at 314 N. Naches Ave. The Yakima Housing Authority owns the three-story building, which includes 50 elderly and disabled housing units in Yakima, Washington.

A portion of the structure to the south and an adjacent parking lot occupy the approximate footprint of what was the boarding school and attached dormitories for Native students. As is the case at Fort Simcoe, there are no markers of any kind indicating that a boarding school for Native students stood on the property.

The list of Catholic-affiliated boarding schools for Native children is not final. There is a contact form on the list website; comments, corrections and additional information may be submitted there. Subsequent editions of the list will be published annually to reflect new discoveries and any corrections that are submitted through that contact form.

All of the information on the list came from publicly available resources, and those involved in researching and sharing it, such as Arsenault of the White Earth Band of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, hope it will open up more resources.

“This list has the potential to open lines of communication between Catholic archives and Tribal Nations,” Arsenault said.