It is so all there, in the first two minutes.

Manhattan, 1971. Noise. Grime. The mean streets two years before Martin Scorsese’s “Mean Streets.”

Isaac Hayes’ “Theme from Shaft” — still the greatest-ever Oscar-winning song, just ahead of “Thanks for the Memory” — strides in underneath the “Shaft” opening credits sequence at the 30-second mark, as the camera glides by a grindhouse marquee advertising “The Wild Females.” He hasn’t even made his entrance yet, and they’re already lining up for him? Damn right.

Then, up from the subway, there he is, in leather and a turtleneck, cutting across a sea of sedans heading downtown. “Up yours!” says the private eye whose resume will forever lead with the lyric “sex machine to all the chicks.” Two years earlier, Ratso Rizzo in “Midnight Cowboy” came up with “I’m walkin’ here!” in a similar situation. Confronted by what you can only assume is the same pushy driver, John Shaft needs only two words (“Up yours!”) and one finger to handle the man.

Two minutes into the opening credits, Richard Roundtree was a star.

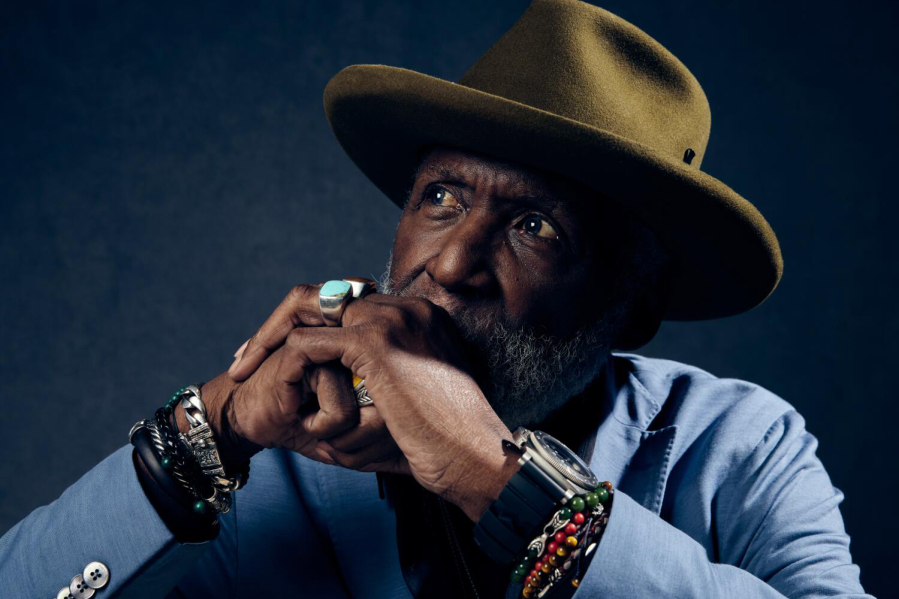

Roundtree died Oct. 24, at the age of 81, from pancreatic cancer. He never quite shook the memory, and the long, confining shadow of “Shaft,” its sequels, the short-lived, sanitized 1973 TV series, the reboots.

“Twenty-four-seven, there’s always some mention of that character,” Roundtree acknowledged on the red carpet of the 2011 Turner Classic Movies film festival. “Shaft” screened in the festival that year.