WASHINGTON — A brutal conflict in Europe was fresh in people’s minds and the race for the White House turned ugly as talk of secret societies and corruption roiled the United States.

It was 1800, and conspiracy theories were flourishing across America. Partisan newspapers spread tales of European elites seeking to seize control of the young democracy. Preachers in New England warned of plots to abolish Christianity in favor of godlessness and depravity.

This bogeyman of the early republic was the Illuminati, a secret organization founded in Germany dedicated to free thinking and opposed to religious dogma. Despite the Illuminati’s lack of real influence in America, conspiracy theorists imagined the group’s fingerprints were everywhere. They said Illuminati manipulation had caused France’s Reign of Terror, the wave of executions and persecutions that followed the French Revolution. They feared something similar in America.

From the witch trials in Salem, Mass., to fears of the Illuminati, from the Red Scare to the John Birch Society to QAnon, conspiracy theories have served as dark counterprogramming to the American story taught in history books. If a healthy democracy relies on the trust of its citizens, then conspiracy theories show what happens when that trust begins to fray.

Change a few details, add in a pizza parlor, and the hysteria surrounding the Illuminati sounds a lot like QAnon, the contemporary conspiracy theory that claims a powerful cabal of child-sacrificing satanists secretly shapes world events. Like the Illuminati craze, QAnon emerged at a time of uncertainty, polarization and distrust.

“The more things change, the more things seem to come back,” said Jon Graham, a writer and translator based in Vermont who is an expert on the Illuminati and the claims that have surrounded the group for centuries. “There’s the mainstream narrative of history. And then there’s the other narrative — the alternative explanations for history — that never really goes away.”

Just like today, these bizarre stories often reveal deeply rooted anxieties focused on racial and religious strife and technological and economic change.

The most persistent conspiracy theories can survive on the fringes for decades, before reappearing with new details, villains and heroes, often at a time of social upheaval or economic dislocation. Sometimes, these beliefs can erupt into action, as they did on Jan. 6, 2021, when a mob of President Donald Trump’s supporters broke into the U.S. Capitol.

In America’s early days, the villain was the Illuminati.

Created in 1776, the group was part of a fad of supposedly secret societies that became fashionable in Europe. It was defunct by 1800 and had no presence in the U.S. Still, claims spread that Illuminati agents were working undercover to take over the federal government, outlaw Christianity and promote sexual promiscuity and devil worship among the young.

The theory was picked up by the Federalist Party and played a key part in the 1800 presidential race between President John Adams, a Federalist, and Vice President Thomas Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican. Rumors circulated among Federalists that Jefferson was an atheist who would hand America over to France if elected president.

Jefferson did win, and the Federalists never fully recovered. Tales of the Illuminati receded, but soon the Freemasons emerged to take their place in the wild imaginings of early Americans.

The Freemasons counted many leading figures, including George Washington, as members. Their influence fueled whispers that suggested the fraternal organization was a satanic conspiracy bent on ruling the world.

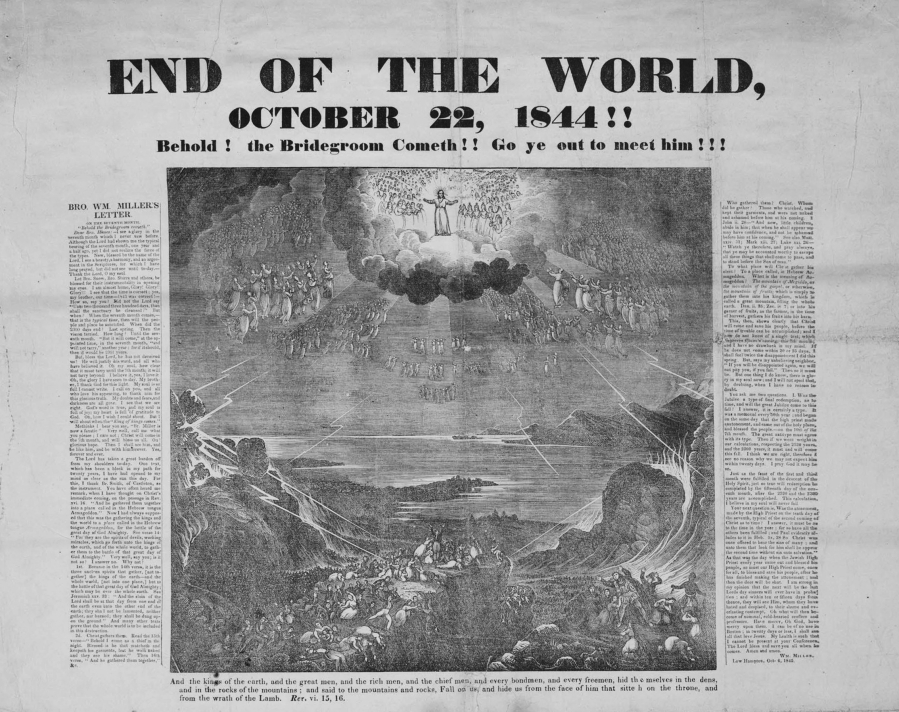

The middle of the 19th century also saw thousands of Americans join new religious movements during the Second Great Awakening. One popular group, the Millerites, was founded by William Miller, a veteran of the War of 1812 who used numeric clues in the Bible to calculate the ending of the world: Oct. 22, 1844.

Before the appointed day, many of Miller’s followers sold or gave away their possessions, donned white clothing and headed for high land so as to hasten their reunion with God. When Oct. 22 passed, some returned to their old lives. Others insisted the End had come, only invisibly.