DALLAS — Deep in the innards of Dallas City Hall — its concrete floor still striped from the years it served as underground parking — a treasure trove of historical curiosities hides.

Clyde Barrow’s wanted poster. Jack Ruby’s fingerprints. Century-old demands from residents for streetlights to discourage teens’ “petting parties” at the neighborhood park.

Photos of comedian Carol Channing awarding crisp $10 bills to schoolchildren’s horticulture projects at the old Farmers Market. Stunning 1910 drawings of long-gone Trinity Play Park, which provided children in the Cotton Mill District their only access to hot showers.

A radio from the Cold War civil defense headquarters buried underneath Fair Park. An original $500 bond certificate from the East Dallas Water Supply Company, dated July 1, 1886, and adorned with scenes of waterfalls and mountains.

That’s a fraction of what’s stored in the Dallas Municipal Archives vault, home to the city’s historically relevant and permanently valuable records. From the amazing to the mundane, you can find it here.

I’ve known forever about the existence of the vault, but always on one deadline or another, I had never visited. After all, city archivist John Slate is only a phone call or email away. He has long been a secret resource for those of us looking to get our facts straight on Dallas, past or present.

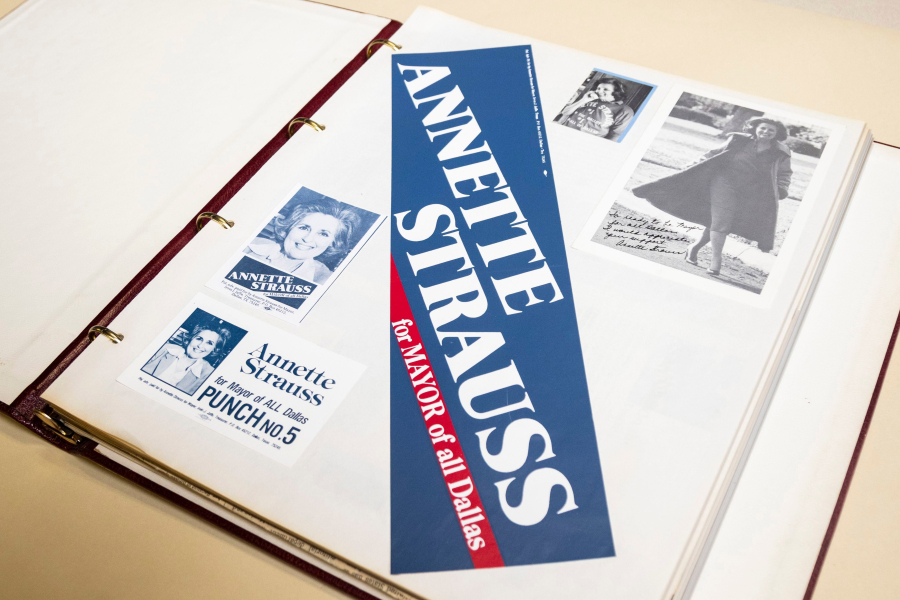

This time though it was Slate reaching out to me with a question. His department had just acquired the papers of former Mayor Annette Strauss. Would I like to see them?

A history-based field trip is always hard for me to turn down, especially when it involves pivotal moments in our city’s political narrative. Strauss’ 1987-1991 tenure marked two firsts: She was the first female and first Jewish mayor elected by Dallas voters.

(If right about now you ask, “What about Mayor Adlene Harrison?” she was appointed to serve as acting mayor for several months in 1976 after Wes Wise resigned to run for Congress.)

Most interesting, and also disturbing, about the Strauss documents is how tightly Dallas still gripped the “It’s a man’s world” mantra when it came to power and politics.

Throughout the pages of her scrapbooks and correspondence, it’s evident how people often underestimated her political and financial savvy. They were quick to view her as a kindly older lady, and she used that to her advantage.

Letters occasionally still addressed her as “Mrs. Theodore Strauss.” Her keen interest in the fiscal health of the city was noted as if it was an extraordinary attribute in a woman. Despite her years as a world-class fundraiser and City Council member, her campaign literature strained to persuade voters Strauss “is ready to be your mayor.”

Slate pointed to the prevailing theme of the collection: “She had this society background, so she had to work harder to convince people that she was serious about governing Dallas.”

The papers shed fascinating light on a Preston Hollow woman who, at 63, led the City Council through a time of painful budget cuts and a protracted, racially charged redistricting battle. Strauss ultimately sided with advocates of the 14-1 single-member districts option, the system still in place today.

After Strauss died in 1998, her papers went to the Annette Strauss Institute for Civic Life at the University of Texas at Austin. They were transferred to the Dallas Municipal Archives late last year, and Slate hopes to have the collection organized by midsummer.

When citizens need information about the past, they often first think of the Dallas Public Library. The city’s business and social history is kept there; the municipal archives holds governmental history.

“We protect the assets of the city and that, in turn, protects the rights of citizens,” Slate said. “They have the right to use these documents to prove or disprove something or some action by city government.”

In the 24 years Slate has been on the job, he’s helped folks research the history of neighborhoods, elections, zoning decisions, City Council votes and milestone Dallas events. About 80% of the requests come from city staff and elected officials; the rest are from people like you and me.

“If you think you aren’t interested in history, think about the park closest to your house and come look at the aerial photos that show what grew up around it,” Slate said.

The climate-controlled vault includes far more than pretty pictures. City staffers research old budgets to find original funding details. Building owners look for exemptions tucked into long-ago zoning codes. After the devastating freeze of February 2021, original plumbing schematics were in high demand as pipes needed repair all over the city.

One of those calls came from Fair Park: “Any chance you have the drawings of the plumbing underneath the band shell?” “As a matter of fact, we do,” Slate responded, pulling out one of the ornate blueprints to show me.

When I first entered the records management location, I was taken back to that final scene in “Raiders of the Lost Ark” — you know, the one where the camera pans across an endless swath of identical crates in a giant warehouse.

The City Hall space allows for storage of about 17,000 boxes. The remainder, more than 60,000 containers worth, are stored offsite. The vast majority contain documents no longer needed on a daily basis but still requiring retention. Many of those are Dallas police case files and municipal personnel records.

Peter Kurilecz, the city’s records management officer, is always on the lookout for items that need to be transferred to Slate’s domain. For example, as he documented 50-year-old records eligible for destruction, Kurilecz found two boxes labeled “historical preservation.” Inside were hundreds of 35 mm transparencies of historic and potentially historic Dallas buildings.

Also last year, while searching for a police case file, Kurilecz came across a familiar name: Santos Rodriguez. Inside were some of the official documents in the case involving a Dallas police officer’s murder of 12-year-old Santos in 1973.

Both discoveries were sent to the historical archives section which, along with Kurilecz’s operation, is part of the City Secretary’s Office.

Kristi Nedderman, assistant city archivist, told me it’s almost impossible to say which item she most admires in the collection. That’s like picking your favorite puppy, she laughed.

If she had to choose, it would be the several thousand blueprints of city buildings and parks, many drawn and colored more than 100 years ago. She’s also fascinated by the artistry of the longhand script that clerks in the late 1800s and early 1900s used when transcribing City Council minutes into oversized ledgers.

Slate had as difficult a time as Nedderman when asked about the most memorable items in the collection. He fell back on the most sought-after: the JFK collection, which is available in digital form, and the Bonnie and Clyde material.

It pains the archivist when he’s asked for a copy of the iconic but spurious Bonnie and Clyde poster out of Arkansas, the one headlined “Wanted for murder and rape” and featuring multiple photos of the couple.

“It says they were wanted for rape,” Slate said, “but no documentation exists for that charge.”

Factual history is what the archivists’ work is all about. Sticking to the true stories of Dallas and making sure interested citizens have access to them, as well.