When the first patients — 12 of them — arrived at Maryland’s Hospital for the Negro Insane in 1911, the asylum had yet to be built.

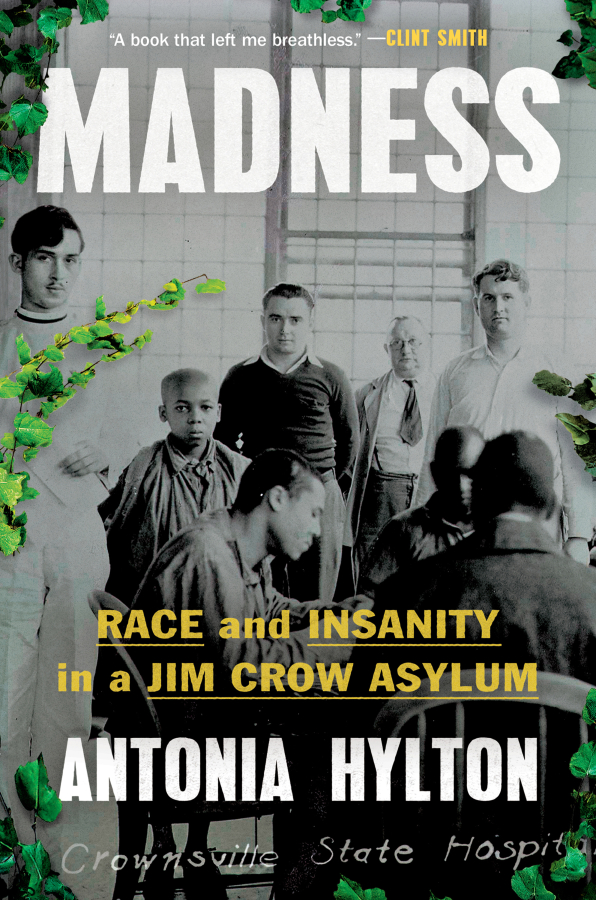

“It would be the first and only asylum in the state, and likely the nation, to force its patients to build their own hospital from the ground up,” Antonia Hylton writes in “Madness: Race and Insanity in a Jim Crow Asylum.” In it, the Peabody- and Emmy-winning journalist traces the nearly 100-year history of the notorious facility later renamed Crownsville State Hospital.

Its construction was in response to a 1906 Maryland State Lunacy Commission report, primarily based on the spurious post-Civil War belief that Black Americans suffered mental illness not from the trauma of enslavement but because they didn’t know how to handle freedom: “The progress of the negro from slavery has been attended with a very marked increase of insanity.” Something must be done, the all-white commission decided, but Maryland, being “too much of a Southern state,” wouldn’t countenance the mixing of races. A separate facility was needed, and it had to be built cheaply.

To white officials and doctors, Hylton writes, therapy for Black Americans meant “labor, and a return to the antebellum social order.” In other words, Crownsville’s “patients” were viewed as unpaid laborers and were put to work, but not just for the asylum. Once the hospital was completed and crops were planted and harvested on the grounds, patients were sent out to labor on adjoining farms — just the beginning of the abuses heaped upon the patients, Hylton would discover.