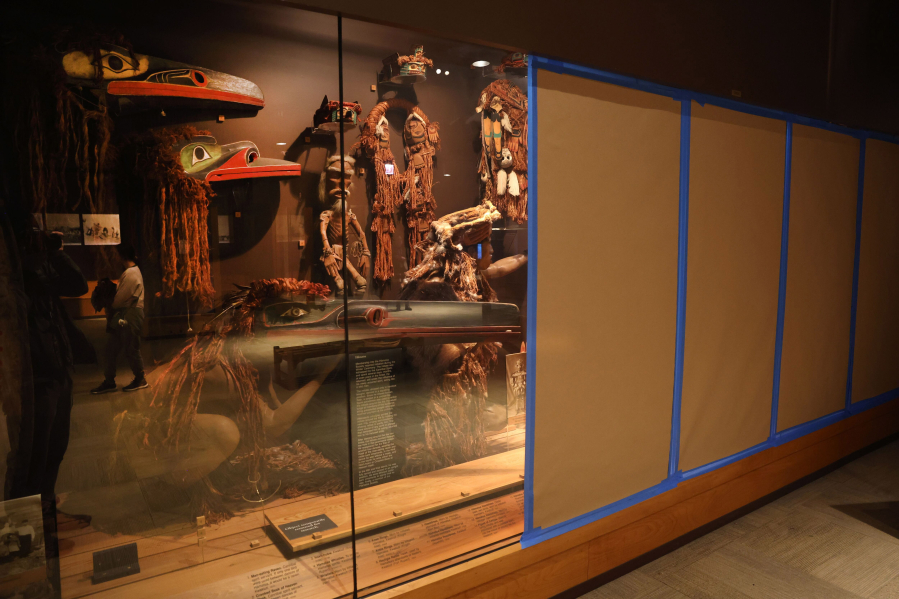

CHICAGO — If you stop by Chicago’s Field Museum right now and find yourself in the Alsdorf Hall of Northwest Coast and Arctic Peoples, or the Robert R. McCormick Halls of the Ancient Americas, you will notice something about the display cases: Several are covered up.

That in itself is not unusual — who hasn’t been to a museum and seen a display case displaying nothing? What’s unusual is the reason: On Jan. 12, federal regulations concerning the exhibition and study of Native American remains and sacred artifacts were tightened, to bring teeth and clarity to a set of rules that languished for decades.

The revised regulations are sweeping: They demand museums speed up the process of repatriating Native American “human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects or objects of cultural patrimony,” establishing ownership and lineage between museum collections and Native American descendants, returning anything requested. Museums must update their inventories of Native American remains and funerary objects within five years. Also, curators can no longer categorize such items as “culturally unidentifiable,” thereby holding them indefinitely. Tribal knowledge and traditions must be deferred to.

Moreover, institutions must get “free, prior and informed consent” from Native tribes before the exhibition or research of sacred artifacts. According to a Field Museum statement, the covered displays hold “cultural items that could be subject to these regulations,” and will stay covered “pending consultation with the represented (tribal) communities.” (The Field also noted it does not have any human remains on display.)