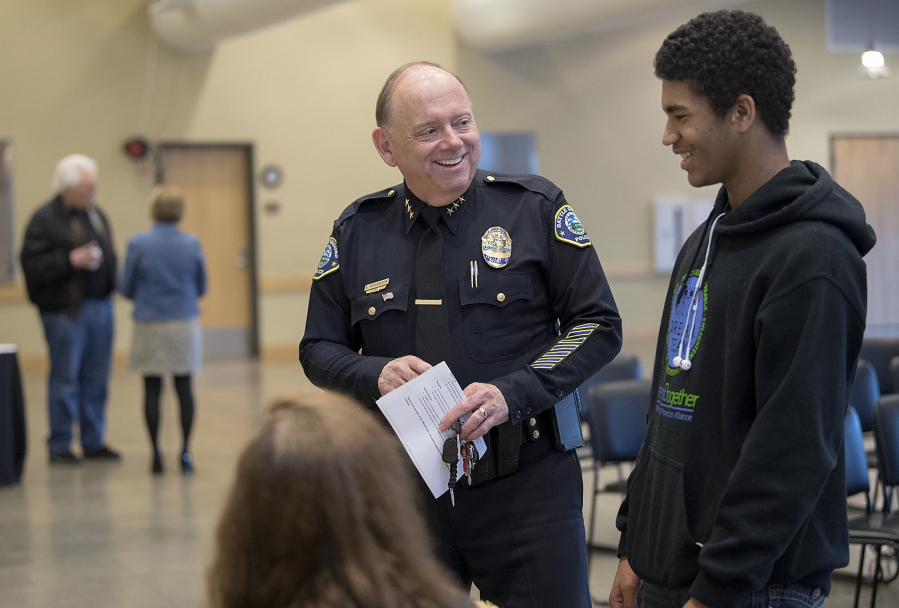

Battle Ground Police Chief Bob Richardson grew up always wanting to be a police officer, watching “Adam-12” and other cop shows on TV with his brothers.

After serving as a military police officer, he joined the police department in Irvine, Calif., then started working his way up. He was an officer, handled traffic, worked as a detective, became a sergeant, trained others, later became a lieutenant and then commander. In 2011, he was hired as Battle Ground’s police chief.

Richardson said it’s fun to create a vision of where a department is going to go and to respond to external changes while you go.

“That’s why I like doing it. Every day’s a little bit different,” he said.

Running a smaller agency presents some unique challenges and rewards, Richardson said. In general, there’s often fewer hands, but expectations for quality policing don’t change based on the size of the town.

Here is how police chiefs in Clark County’s smaller cities describe their jobs.

Challenges

Chief John Brooks started as Ridgefield’s chief in October, after 26 years with the Portland Police Bureau.

“In a small community, little things are big things, and that’s really important to know,” he said.

In his first week on the job, a loose dog killed some sheep.

“Not the case of the century, but it was important to people that owned the sheep and it was important to other pet owners,” Brooks said.

Small-town officers have to become generalists and learn many aspects of policing, dealing with loose dogs to burglaries to occasional violent crimes, he said. That’s because there’s no need for, as examples, a bomb squad or full-time homicide detectives.

Similarly, most chiefs will start work after a varied police career, he said. Brooks worked on homicide and drug investigations, handled the records section, ran the department professional standards division and supervised the family services division.

Law enforcement leaders, at agencies large or small, ought to be able to understand multiple aspects of policing, he said, but they also need to know budgets, human resources and how they fit in with the rest of a city or county government.

“You can’t just approach this job as, ‘I’m in this island and I just deliver law enforcement. I just look for people who break the law and then I arrest them,'” he said. “That’s a very one-dimensional way to look at being a chief, and you would not be successful.”

But because everyone’s a generalist, circumstances arise where small departments sometimes need to find help, Camas police Chief Mitch Lackey said.

“Not often, but sometimes you need a certain tool, and only that tool, and if you don’t have it, you have to go out and, hopefully, have somebody who can help you with that,” he said.

That might mean looking for grants or asking a neighboring agency’s police dog team for backup.

Thankfully, Lackey said, the local law enforcement community is quick to share.

“I have, in 27 years, rarely heard ‘no’ as an answer to that.”

Advantages

On the other hand, Lackey said being smaller means a chief can act a little faster.

“One of our advantages is we’re more nimble,” he said. “Our organization isn’t so bureaucratic. There’s fewer layers, and so I think we’re a little quicker to be able to respond to community needs.”

He pointed to the growing issues of police encounters with people having drug-related or mental health crises.

The need for better training for better outcomes was increasingly clear; the Legislature was starting to debate mandating training for officers and more in the public were expecting the police to do more.

So, when the state mandated officers have some mental health crisis response training, his department had a head start. And because Camas is smaller, it was less challenging logistically.

“Trying to train up 27 people is a lot easier than Chief McElvain trying to train up over 200 officers,” Lackey said, referring to Vancouver’s police chief.

Being small can also present an advantage when recruiting officers, Richardson said, depending on the officer.

In general, larger departments can offer better pay and benefits. Since the recruiting pool of new officers has dropped in recent years, pay has grown into an arms race among departments: When a large agency increases salaries, all the outlying agencies have to find ways to keep up.

Brooks said some cops might be thinking about their paycheck, while others might be looking for a place where they can generalize, do more work on each case or for a different setting.

Lackey recalled hiring an officer who transferred from the Portland Police Bureau after time with the agency’s tactical unit and many high-energy calls.

“When we interviewed, I’m like, ‘Are you sure you want to be here?’ I mean, look at Camas: It’s a pretty peaceful, pretty quiet place,” Lackey said. “And he said, ‘Yeah chief, this is exactly the type of place I’d like to be.'”

Richardson said chiefs and police recruiters need to market their agency.

“We may not be the biggest agency. We may not be the highest-paid agency, but we’ve got a community that’s very supportive of us. People wave to us, they buy you lunch, so you have to kind of market your community,” he said, and some officers are drawn to that.

Closer to the action

Lackey, Brooks and Richardson all said they’re closer to the action thanks to the size of their agencies and can actually connect with their line officers. Even if that means, Lackey said, it makes him a bit jealous at times.

“Most people will tell you they kind of still miss the police work part. One of the selling-your-soul type issues that you do when you go into management, you give up that things you first went into the career for,” he said. “That’s not so much the toughest part about being chief, but it’s one of those things you miss. You miss doing the true police work.”

Richardson said his department’s size also means its easier for a chief to stay connected with the community.

The city of Woodland is looking for a new chief after former Chief Phil Crochet retired last year. Woodland started its first review of applicants this week, and will being interviews March 9, City Administrator Peter Boyce said.

Richardson said Woodland residents and officials would do well to get involved in the hiring process as much as they can.

“People need to realize that, hey, if you want that to be a good experience and you want to be proud of your police department, you need to have a leader in there you can trust,” he said. “The only way you can get that is you get engaged in the process.”