In the Vancouver of 1890, shadows of the Wild West could be glimpsed in the midst of urban development.

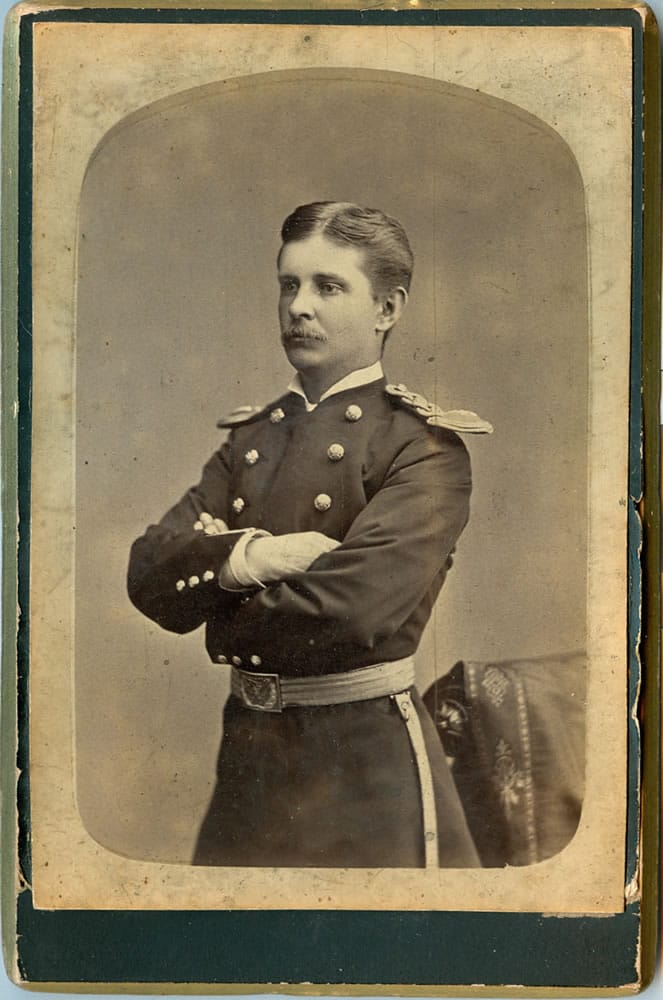

Lt. Frederic Calhoun retired from the U.S. Army in 1890 at Vancouver Barracks, 14 years after the military careers of his brother and his brother-in-law — Gen. George Custer — came to bloody ends at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Calhoun missed the battle because he had been assigned to the 14th Infantry Division, explained Vancouver author and military historian Jeff Davis. Calhoun was 100 miles away from the battlefield when the 7th Cavalry was massacred on June 26, 1876.

(Davis said that many of the men at Vancouver Barracks in 1890 and well beyond were career soldiers whose service in the Civil War and the Indian campaigns left them with what we now recognize as PTSD. With no counseling or therapy, the medication most of them took was alcohol, Davis said, “and lots of it.” More than 1 1/2 years after his relatives were killed, Calhoun wrote that he was “sober at last.”)

Ghosts of another Indian War came home in November 1890. A newspaper reported that the bodies of military personnel killed in the 1877 Nez Perce War were removed from the cemetery at Fort Lapwai in Idaho and reinterred at Vancouver Barracks.

Clark County had its only public execution that year. In what was called the hanging holiday of 1890, Edward Gallagher was executed for the murder of a farmer. Up to 500 people — nearly 9 percent of Vancouver’s population — gathered at the courthouse plaza to witness the hanging, according to a 2013 recounting in The Columbian.

The American frontier was still something people could discuss in present tense. The frontier wasn’t officially declared over until later in 1890. That’s when the superintendent of the U.S. Census said that the American West had so many pockets of settled areas that “there can hardly be said to be a frontier line.”

It had been a rapid transition. An interactive map on the Census Bureau website shows only one population cluster in 1880 north of Denver and west of Minnesota: It’s the Willamette Valley/Clark County area.

The next map, based on the 1890 census, shows one extended populated area along what’s now the Interstate 5 corridor, from the Willamette Valley to the Canadian border.

Progress came to town: Work on the first city sewer system — 2 miles of it — was well underway in 1890.

A “cow ordinance” was re-enacted, after the city was (as a newspaper story reported) periodically “overrun with horses, cattle, sheep and a pig here and there.”

Two organizations were established that have influenced the community in different ways for 125 years: the Chamber of Commerce and the Salvation Army.

Not that it was all good news. A newspaper reported that Vancouver police made 38 arrests in December 1890. It was the most ever in a month, and the story offered this observation: “We are growing.”

Tom Vogt: 360-735-4558; twitter.com/col_history; tom.vogt@columbian.com