As Juan Pacheco prepared to speak at Clark College, he tied a black bandana around his head, put on a blue cap and tucked a blood-red bandana into the pocket of his Dickies. Slowly, during his talk, Pacheco removed those articles of clothing — the ones that make people jump to conclusions about who he is and what he represents.

“If I look like a duck, and I quack like a duck, I must be a duck,” Pacheco said. “Respect has to do with looking upon me one more time.”

He was a gang member, and that’s his old look. These days, he is a pre-med student, more likely to don slacks and a crisp button-down.

Pacheco is the keynote speaker for the Keeping Our Kids Safe Conference put on by the Safe Communities Task Force. The two-day conference talks about ways to work with youth and understand those who grow up experiencing trauma. The conference includes a panel of youth talking about how they’ve turned their lives around.

Friday morning, Pacheco addressed educators, counselors, law enforcement, those involved in the juvenile justice system and other professionals working with youth. The theme this year is transformation.

“Every transformation starts with a change in your thought process,” said Josh Beaman, Safe Communities Task Force coordinator.

Pacheco’s story begins in poverty in war-stricken El Salvador, where he spent his early childhood living in a home made of mud and rotting wood. The war between rich and poor in his homeland is not unlike the class strife in the United States, he said. It’s these cultural systems where people are afraid to get involved that perpetuate generations of violence and poverty, he said.

In El Salvador — and in several U.S. states — there are scorpions. The baby scorpions are more dangerous than the adult scorpions because they don’t know how to control their poison, Pacheco said. Youth involved in gangs are “young scorpions” with no caring adults around to control their pain and guide their actions, he said.

“Gangs are the effect of ineffective us,” Pacheco said.

When Pacheco’s family moved to Fairfax, Va., family members thought life would improve. But they simply moved from one ghetto to another. Pacheco asked the audience what they hear about from children who are struggling and living in the slums. Drugs. Violence. Harassment. Loneliness. Betrayal. They’re themes that Pacheco knows well.

“Every day that I woke up, I thought that I was less than I was,” he said.

Pacheco compares being in a gang to being in an abusive relationship. Gang members will discipline fellow members for doing something they don’t like, and then turn around and act buddy-buddy again. They offer a sense of belonging, achievement and structure that keeps people coming back, perpetuating the cycle of abuse. Gang members who want to get out, though, are not treated the same way as domestic violence victims, he said.

Pacheco has been convicted of three felonies and he’s gone through jail multiple times.

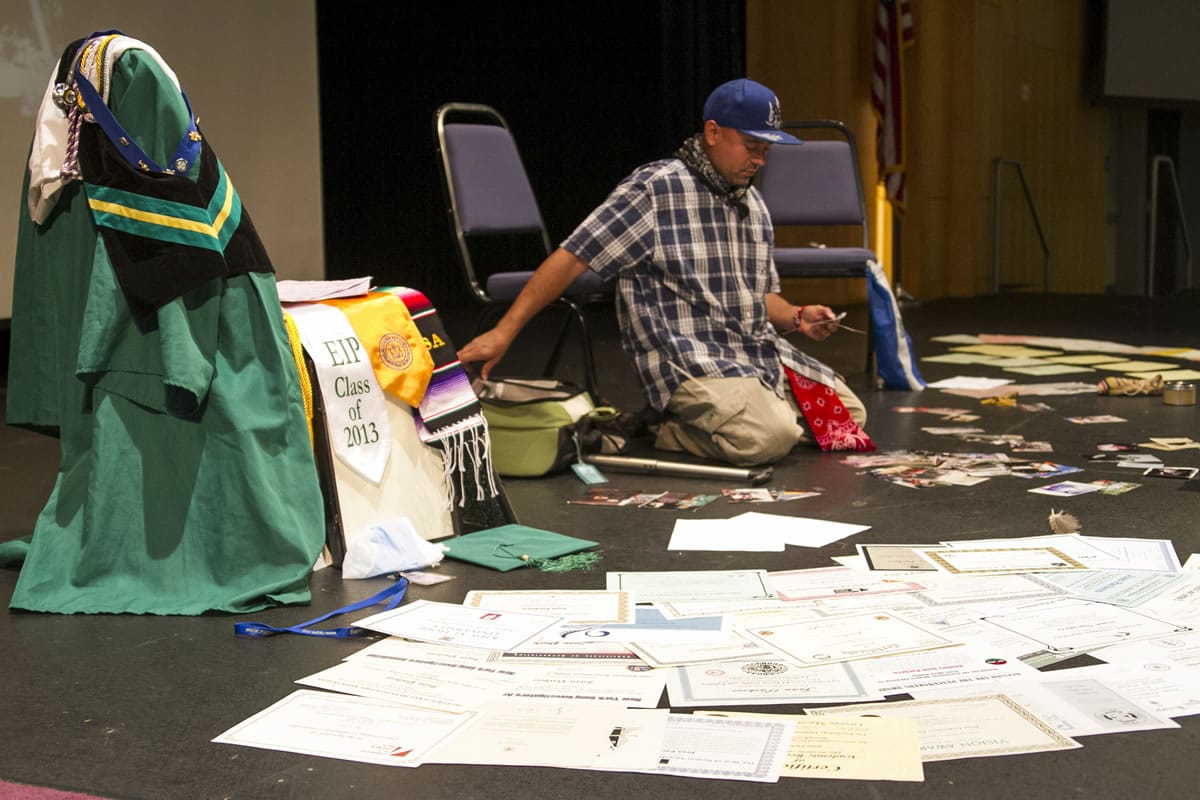

“This record is going to follow me the rest of my life,” Pacheco said, showing the audience his pages of police records. “I became a slave of my own community and expectations.”

In jail, his family visited but he never saw his so-called friends. After getting out, he got some much-needed help from adults who were hard on him and pressed him to do his best but also nurtured him. It wasn’t easy. He relapsed. His mentors told him he had to get his GED and get straight A’s. He did.

He later graduated summa cum laude from George Mason University and holds bachelor’s degrees in nursing, biology and psychology. It was all achieved while he was still poor because people helped him get unstuck and didn’t let poverty control his future, he said.

“It doesn’t take money or fancy programs. It doesn’t take fancy buildings. It takes you — your heart and your love,” Pacheco said.

Whatever role an adult holds, troubled youth need to hear that the gang life is not the life for them, he said. With his green graduation gown and hospital scrubs layered over his clothes, Pacheco shows what life can be. He plans to earn his doctorate and return to El Salvador to treat people in his homeland.