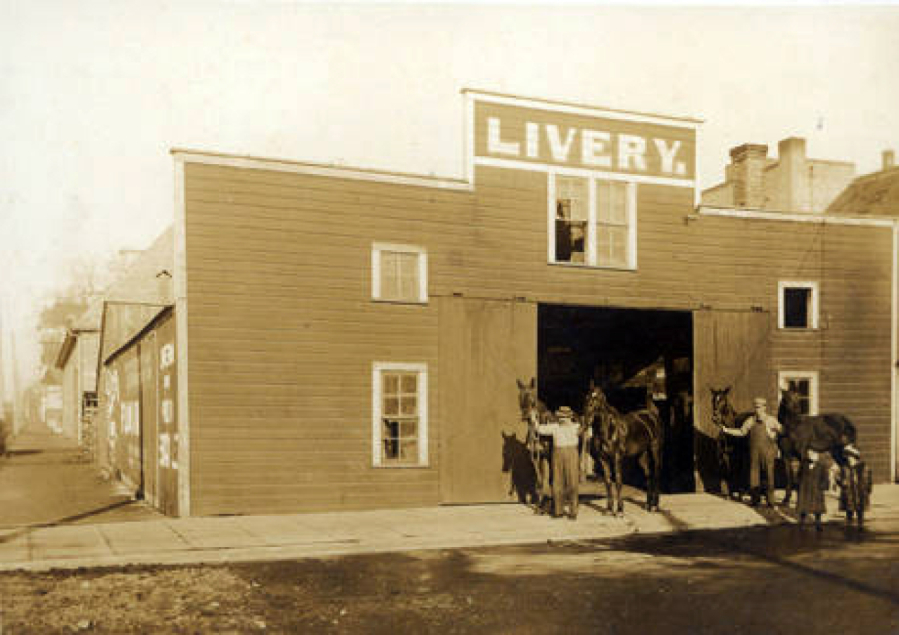

During the late 1800s, passing by any Vancouver, Camas, Ridgefield, La Center or Amboy livery stable would clear your sinuses. But, then again, perhaps the pungency was diluted by the livestock drippings and droppings left on the streets and the waste residents pitched onto the roadway, awaiting the rain to wash it away.

Automobiles sideswiped the livery business, replacing the stench of road apples for the aroma of hydrocarbon exhaust. Although the county possessed earlier liveries, the Smith brothers, Joseph and James, built a livery barn at Washington and Third streets near Vancouver’s ferry dock sometime around 1890. The Smith Livery Stable became a convenience for southbound travelers needing to drop off a horse and Portlanders to pick one up.

Like others, the Smiths hired out horses, teams, buggies and wagons to folks promising to return them. Sometimes they sold hay and feed. Liverymen, like the Smiths, slapped arrest warrants on anyone not returning them. To ensure payment, all livery owners held liens on animals, conveyances or goods left in their care until the owner paid.

After 1900, James Smith bought his brother’s share of the business. Eventually, his son Bud owned the livery and proudly added “Bud” to the company name. Bud Smith added a hearse for its beauty, extending his offering beyond buggies and wagons, although he wasn’t sure how to use it.