Road No. 25 is a paved north-south route from the Lewis to the Cispus rivers through the heart of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. And before road No. 25 was built, there was road No. 125, a less-nice road covering roughly the same terrain.

And before that, it was called the Clear Creek Ridge road, according to John Barbieri of Vancouver, a land surveyor and engineer, who spent almost two years working for the Forest Service in the mid-1950s, including the preliminary survey for the road.

“It was hard work,” said Barbieri, now 82, of Barbieri & Associates Inc., a Hazel Dell civil engineering, land surveying and land development company. “A lot of the work was not on trails and there were no roads then.”

Barbieri, an Illinois native, worked for Weyerhaeuser Co. before the Forest Service.

“I looked at the hillsides and all you could see was old-growth timber,” he said in an interview. “I said, ‘There is no way this will ever by logged in my lifetime.’ That was 1952 and by 1980 it was gone.”

Barbieri and his wife, Mary Ann, remember living at Twin Buttes Guard Station in a two-room cabin. There was another adjacent cabin plus a guard station nearby at Mosquito Lakes.

He remembers doing the survey for Steamboat Mountain Lookout, some roads and a bridge in the Trapper Creek area and work in the Iron Creek area.

There was a white tent involved in the Iron Creek work at the same time Dwight Eisenhower was having cardiac problems, he said.

“It was called the Little White House,” Barbieri said. “That was in October when we went in. The days were short, the nights were cold and the sun didn’t get down into the canyon.”

His surveying work in the forest gave him an appreciation of roof over his head.

“I had my fill of camping,” Barbieri said. “I never wanted to go camping again.”

He remembers time at Camp 5 near Coweeman Lake when working for Weyerhaeuser. He took a walk in the woods and found some massive noble fir stumps.

“I found these huge, huge stumps where they came in and selectively had taken out the noble fir for making gliders,” he said.

Many forest roads today are two lanes and paved.

But not in Barbieri’s day.

“For the longest time, the roads we worked on were one lane with turnouts and not asphalt paving,” he added.

In 1954, there was a big push to improve trails throughout the Goat Rocks, Barbieri said.

“Justice William O. Douglas fell and got hurt on a trail and then there was all kinds of money to beef up the trail,” he said.

Barbieri’s office has boxes of notepads containing write-in-the-rain treated paper. But before that was available, they made their own by dipping paper in kerosene and letting it dry.

“You didn’t smoke around it,” he said.

He had a survey project as a private contractor for the Forest Service in the Smith Creek area just before Mount St. Helens erupted.

“It blew the hillside and that part of the job was gone,” he said.

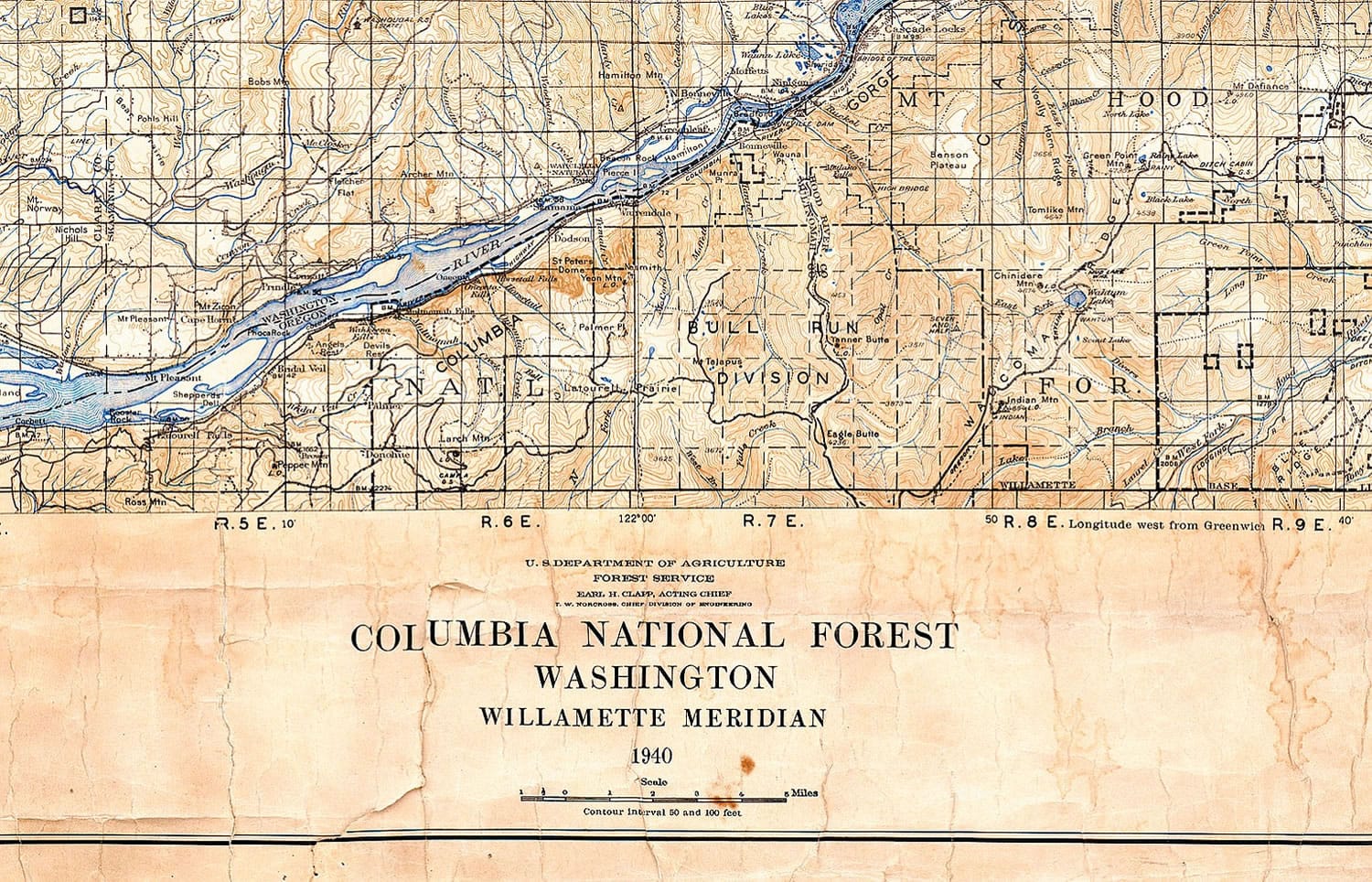

On the wall of his office, Barbieri has a reproduction of a 1940 map of the Columbia National Forest, which was the name of the federal forest in Southwest Washington before it was renamed in honor of the first chief of the Forest Service.

The original map belong to the friend of a former employee of Barbieri’s.

It’s an interesting document for those who appreciate the history of the GPNF. Yale and Swift reservoirs are not the map, since their hydroelectric dams had not been built yet.

There’s a large flat along the North Fork of the Lewis River between about Marble and Camp creeks labeled “Big Bottom.”

Today’s road No. 90 ends on the map just east of Cougar in Cowlitz County.

Today’s roads Nos. 60 and 24 are the main north-south route through the interior the of the forest. Twin Buttes-Mosquito Lakes, with guard stations and nearby lookouts and campgrounds, is clearly a hub of human activity.

Barbieri said the Gifford Pinchot National Forest has too many roads, but don’t blame the Forest Service.

“They got their marching orders from Congress,” he said. “Congress wanted revenue, so there had to be timber sales and timber sales needed roads.”